This Final Study is the result of the ‘Study on the enforcement of State aid

rules and decisions by national courts (COMP/2018/001)’ (the ‘Study’), carried

out for DG Competition of the European Commission by Spark Legal Network, the

European University Institute, Ecorys and Caselex, with the support of a network of

national legal experts. The Study offers a comprehensive overview of the enforcement

of State aid rules by national courts of the 28 Member States, identifying emerging

trends and challenges and presenting best practices. It also provides insights on the

use of cooperation tools by the Commission and national courts. In order to meet the

objectives of the Study, the following tasks were carried out: Task 1 – Identify,

classify and summarise the most relevant rulings rendered by national courts on State

aid matters; Task 2 – Summary of the main findings at EU level; Task 3 – Identification

of best practices; and Task 4 – Use of the cooperation tools by the Commission and the

national courts. The Study includes 145 case summaries and 28 country reports in its

annexes which are publicly available on a dedicated project website, including a

user-friendly Case Database.

Introduction

This document comprises the Final Study for the ‘Study on the enforcement of State aid rules and decisions by national courts (COMP/2018/001)’ (the ‘Study’), carried out for DG Competition of the European Commission (the ‘Commission’) by Spark Legal Network (the ‘Data Collection Team’), the European University Institute (the ‘State Aid Team’; Spark Legal Network and the European University Institute are together referred to as: the ‘Study Team’), Ecorys (the ‘Cooperation Tools Team’) and Caselex (the ‘Editorial Team’) (together: the ‘Consortium’). The Consortium was supported by a network of national legal experts who were responsible for legal data collection and analysis on the enforcement of State aid rules at national level, producing case summaries and country reports.

The Study comprises four chapters. Chapter 1 includes the legal context, the objectives and the methodology of the Study. Chapter 2 presents a summary and analysis of State aid enforcement by national courts across the European Union (‘EU’), including the main trends with regard to the enforcement of EU State aid rules by national courts. Chapter 3 provides best practices in State aid enforcement by national courts across the EU. Chapter 4 focuses on the findings with regard to the use of cooperation tools by the Commission and national courts in relation to State aid cases. The Study includes four annexes that contain the details of the methodology and the results of the data collection.

Legal context

Under Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’), State aid granted by Member States of the European Union (‘Member States’) is prohibited. Under Article 108(3) TFEU, Member States must notify to the Commission any plan to grant new aid which fulfils the conditions under Article 107(1) TFEU. In addition, Member States are subject to a standstill obligation, whereby they cannot implement the aid measure before the Commission has completed the compatibility assessment of the notified aid. The Commission has the exclusive competence to assess whether an aid prohibited under Article 107(1) TFEU is or may be considered compatible with the internal market.

Under Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (‘TFEU’), State aid granted by Member States of the European Union (‘Member States’) is prohibited. Under Article 108(3) TFEU, Member States must notify to the Commission any plan to grant new aid which fulfils the conditions under Article 107(1) TFEU. In addition, Member States are subject to a standstill obligation, whereby they cannot implement the aid measure before the Commission has completed the compatibility assessment of the notified aid. The Commission has the exclusive competence to assess whether an aid prohibited under Article 107(1) TFEU is or may be considered compatible with the internal market.

- Implementation of recovery decisions (i.e. public enforcement of State aid rules): once the Commission adopts a recovery decision (ordering a Member State to recover an incompatible aid previously implemented in breach of the standstill obligation), the national courts will be involved in the recovery proceedings.

- Enforcement of Article 108(3) TFEU (i.e. private enforcement of State aid rules): interested third parties can start an action in a national court in view of the direct effect of the standstill obligation under Article 108(3) TFEU. In particular, competitors can ask for the recovery of the aid implemented in breach of the standstill obligation (i.e. unlawful aid), independently of the compatibility assessment carried out by the Commission. Finally, competitors can also start damages actions. In the context of private enforcement, national courts rule on whether the challenged measure fulfils the conditions to be considered State aid under Article 107(1) TFEU, thus representing unlawful aid, since it has not been notified to the Commission.

Objectives and methodology

The objective of the Study was to provide the state of play of State aid enforcement by national courts in the EU. It therefore offers a comprehensive overview of the enforcement of State aid rules by national courts of the 28 Member States, identifying emerging trends and challenges, and presenting best practices. The Study looks at national enforcement cases, which were decided between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2017, and includes important cases decided in 2018 (also referred to as: the ‘Study Period’). It also provides insights on the use of cooperation tools by the Commission and national courts. In order to meet the objectives of the Study, the following tasks were carried out:

- Task 1 – Identify, classify and summarise the most relevant rulings rendered by national courts on State aid matters

- Task 2 – Summary of the main findings at EU level

- Task 3 – Identification of best practices

- Task 4 – Use of the cooperation tools by the Commission and the national courts

In Task 1, the Study Team, in cooperation with the national legal experts, identified and compiled a list of relevant rulings adopted by national courts in the Member States in the Study Period (the full list of relevant rulings can be found in Annex 2). Such rulings have been identified in all but one Member State, i.e. Luxembourg. From the list of relevant rulings, the Study Team and the national legal experts selected a sample of rulings on the basis of their legal relevance and novelty within the respective Member States and at EU level (‘selected rulings’). Subsequently, the national legal experts drafted case summaries of the selected rulings, on the basis of a template created by the Study Team. They also created country reports for each Member State, again following a template, providing general conclusions on the state of play of State aid rules at national level (the country reports, including the selected rulings and the case summaries can be found in Annex 3). Additionally, during Task 1, the Editorial Team developed a project website and a Case Database. The project website is publicly available and contains the results presented in the Final Study, as well as a Case Database, and will be kept accessible for at least two years after publication of the Study. The Case Database comprises the 145 case summaries produced under this Study and offers visitors a broad range of search options to find and read the case summaries in a user-friendly way.

The execution of Task 1 formed the basis of Tasks 2 and 3 which were both undertaken by the State Aid Team (supported by the Data Collection Team). Task 2 consisted of analysing and summarising the main findings with regard to the enforcement of EU State aid rules by national courts across the EU, in particular on the basis of the list of 766 relevant rulings, the 145 case summaries and 28 country reports produced under Task 1. The analysis covered both public and private enforcement of State aid rules and consisted of the elaboration of a number of statistics, as well as the identification of a number of qualitative trends, and a comparison with earlier relevant research. The objective of Task 3 was to identify a number of best practices in relation to the enforcement of State aid by the national courts of the Member States. In order to identify best practices, the State Aid Team developed a set of indicators to assess how a given jurisdiction performs: a) the speed with which cases are likely to be resolved as a result of the practice; b) the quality of coordination with parallel Commission procedures; c) the degree to which the remedies provide for adequate compensation; and d) the tools used for judicial dialogue. In the assessment, the State Aid Team looked not only at the practice, but also at the context in which it takes place (i.e. the relevant national judicial framework).

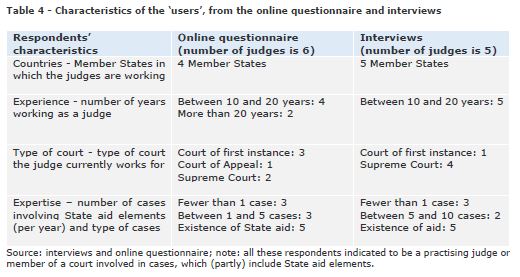

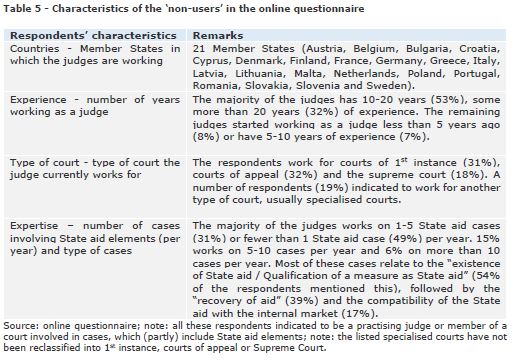

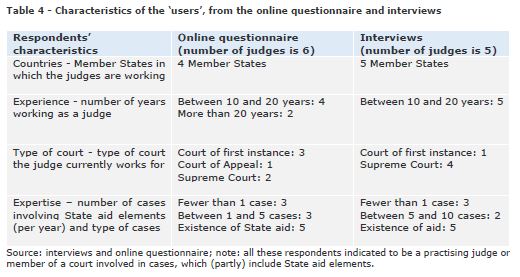

The objective of Task 4, carried out by the Cooperation Tools Team, was to undertake research, gathering knowledge of the use of and views on the cooperation tools provided for in Article 29 of the State aid Procedural Regulation. In order to fulfil the research objectives for Task 4, various data collection methods were employed: desk research (using data available within the Commission), interviews with Commission staff, an online questionnaire addressed to judges at relevant courts (105 respondents, of which 78 were relevant to the Study), and interviews with several judges across the EU (27 interviews).

State aid enforcement by national courts

In Chapter 2, the Consortium identifies a number of trends concerning public and private enforcement of State aid rules by national courts of the Member States. While public enforcement refers to disputes in national courts concerning recovery orders, private enforcement refers to court disputes arising from breaches of the standstill obligation under Article 108(3) TFEU.

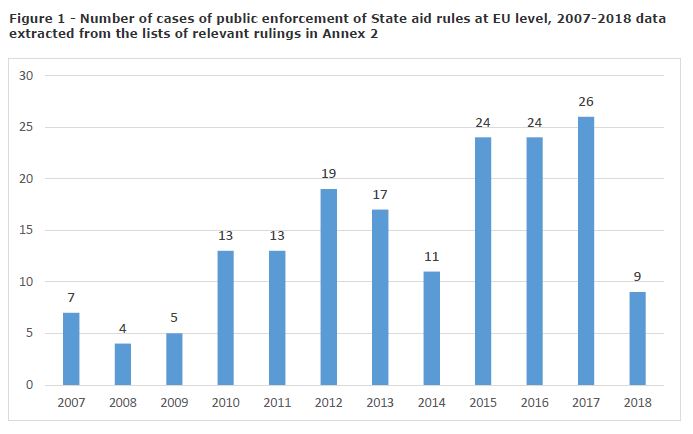

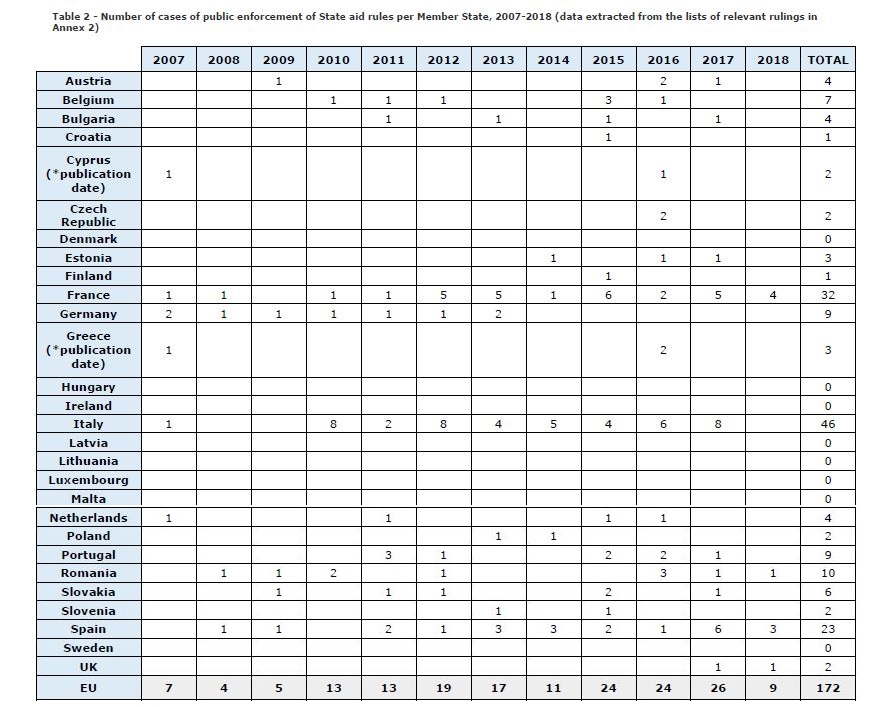

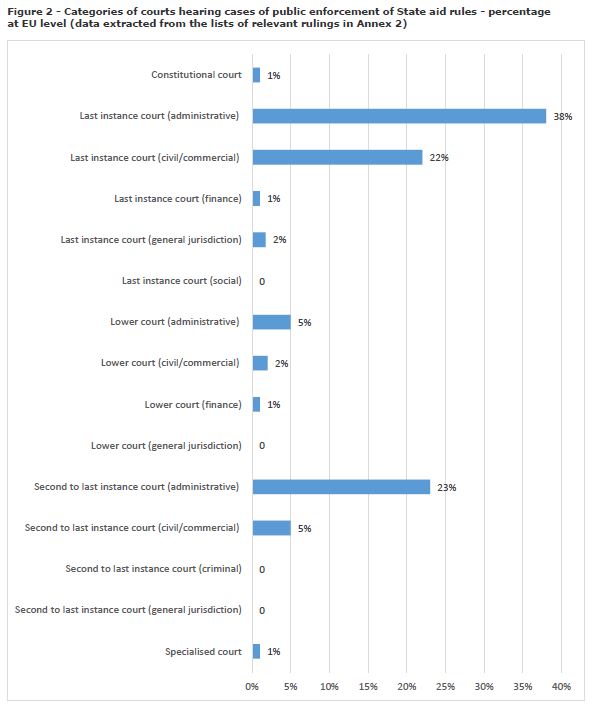

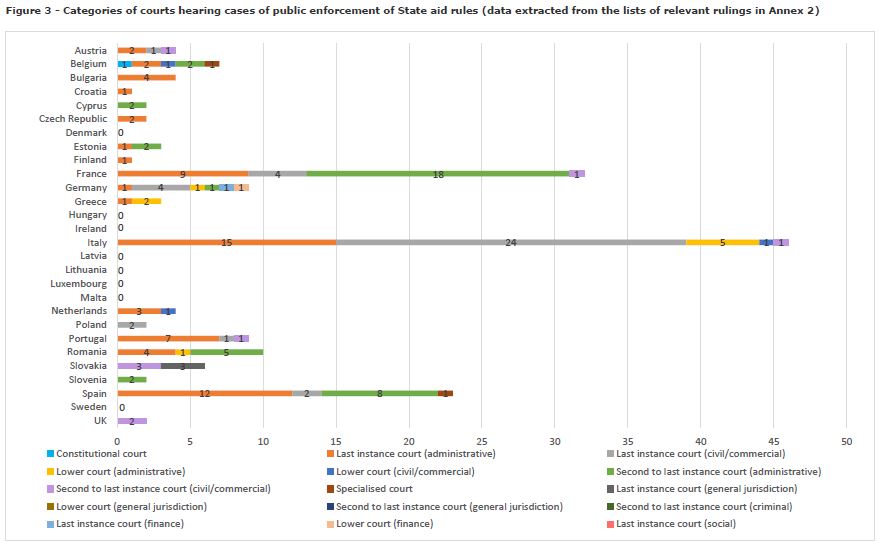

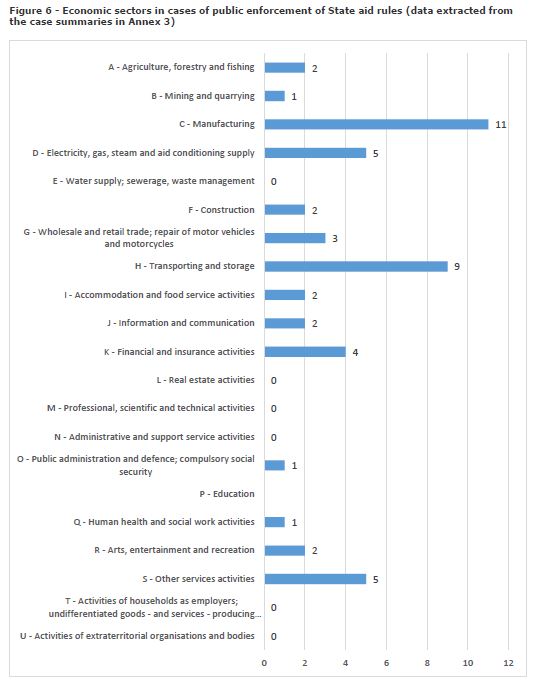

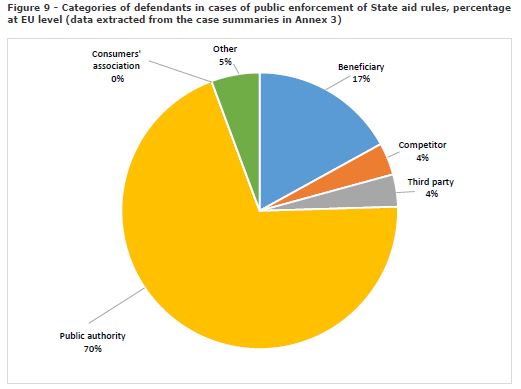

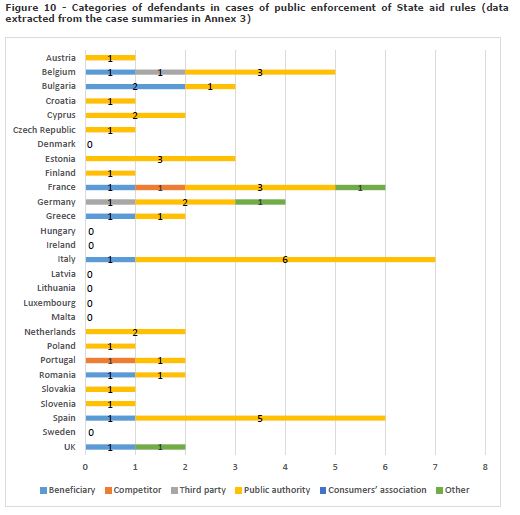

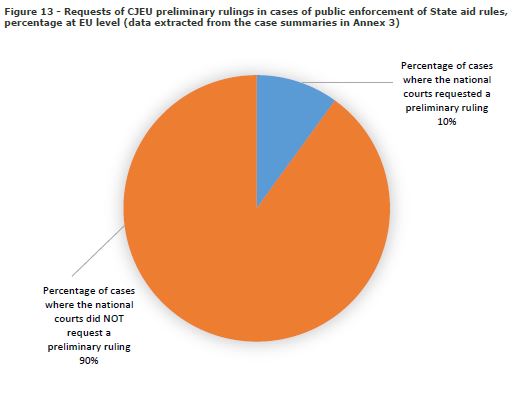

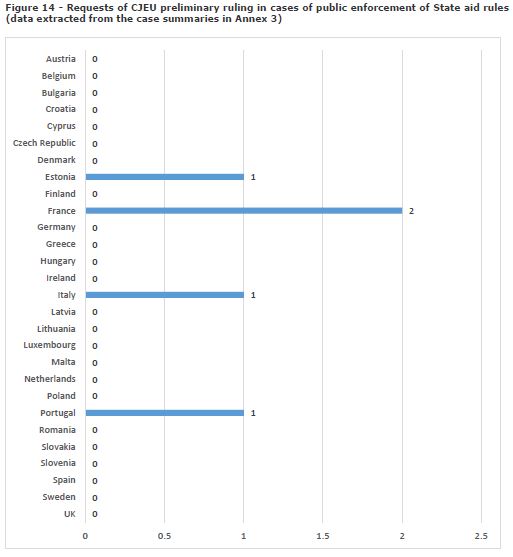

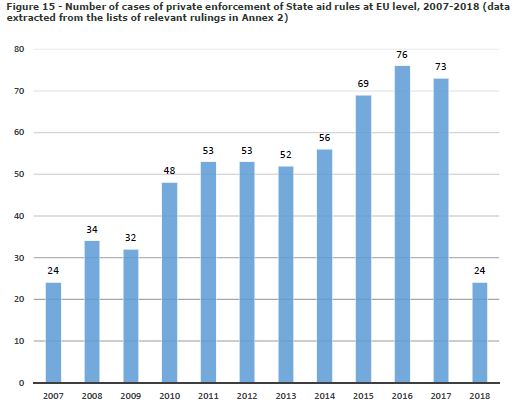

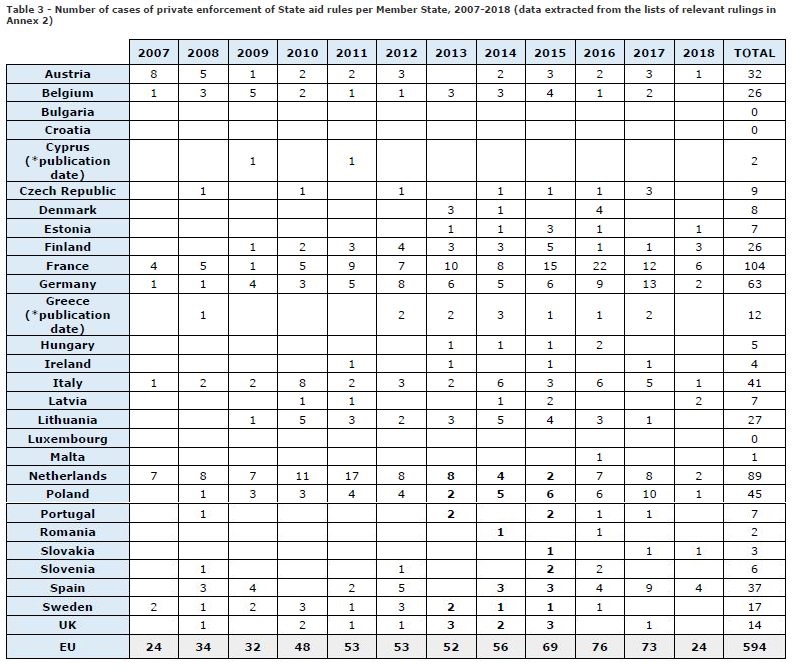

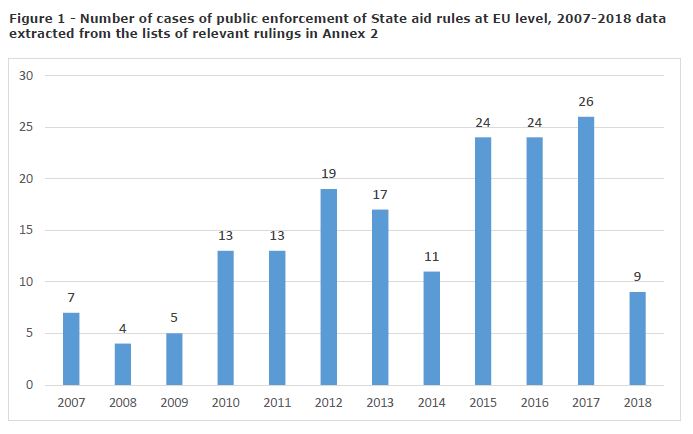

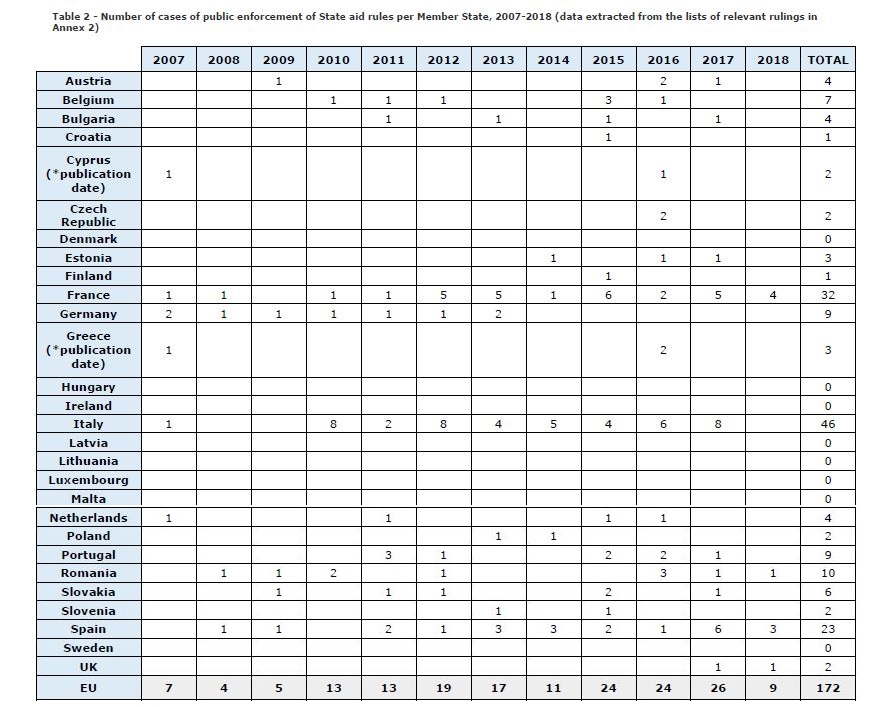

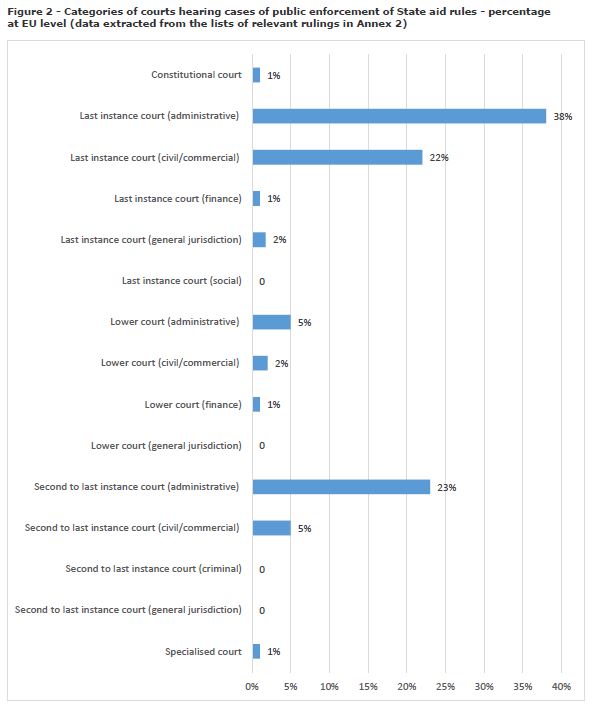

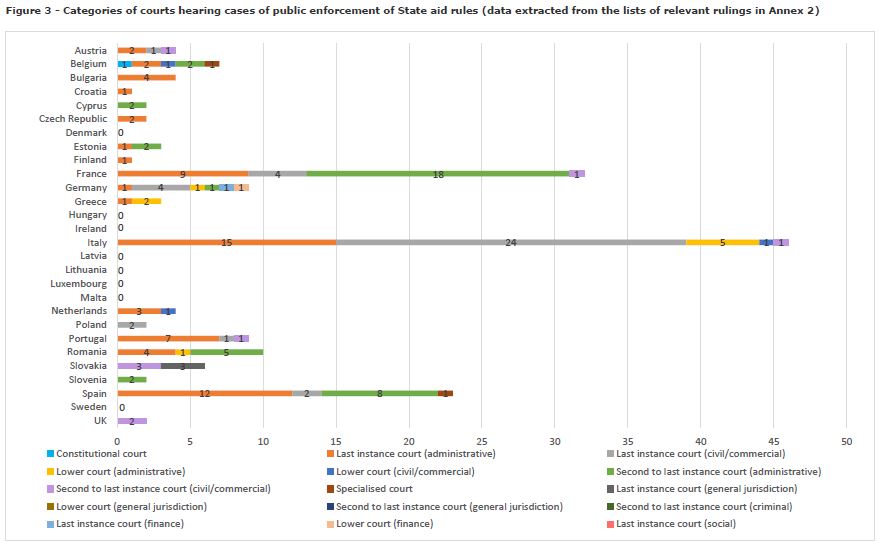

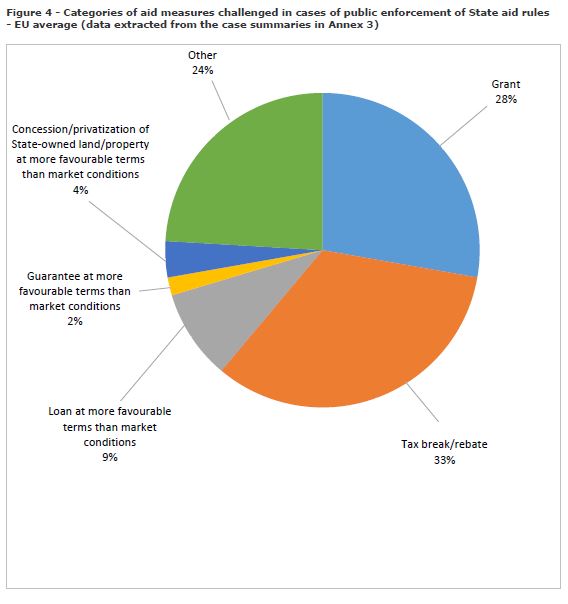

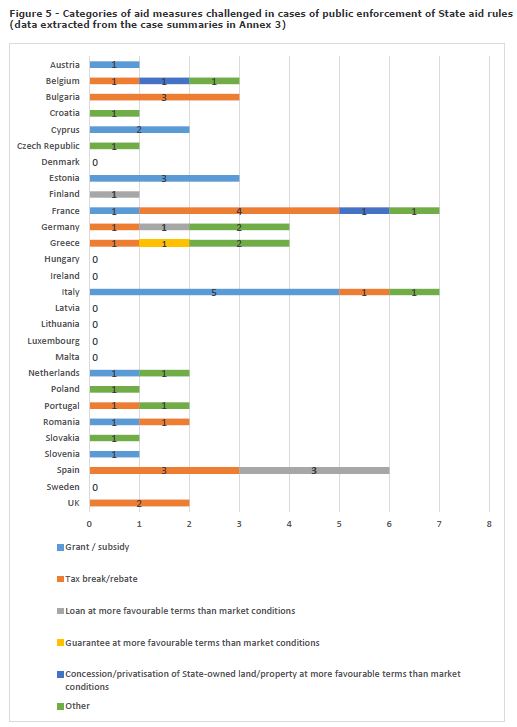

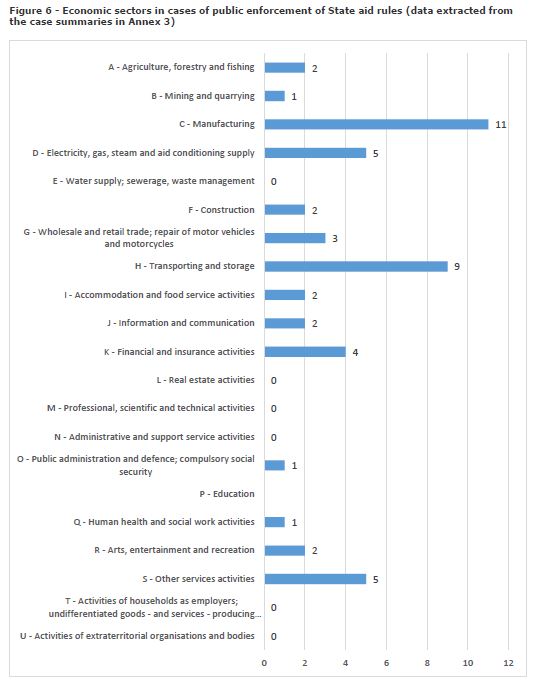

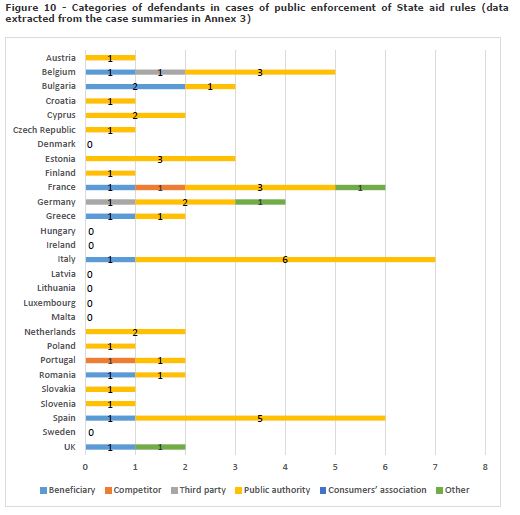

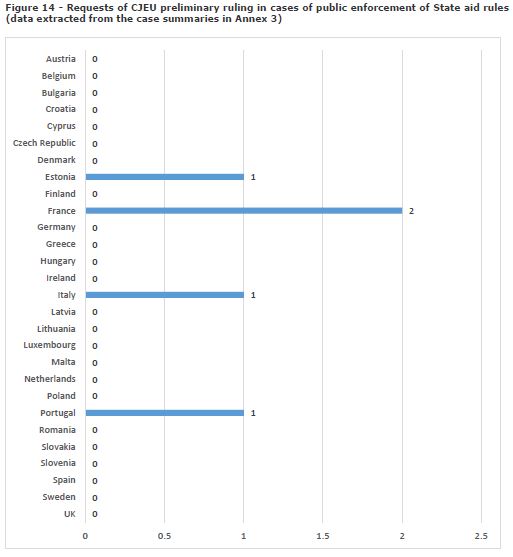

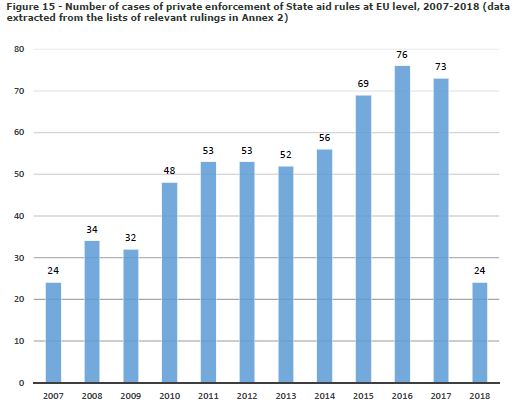

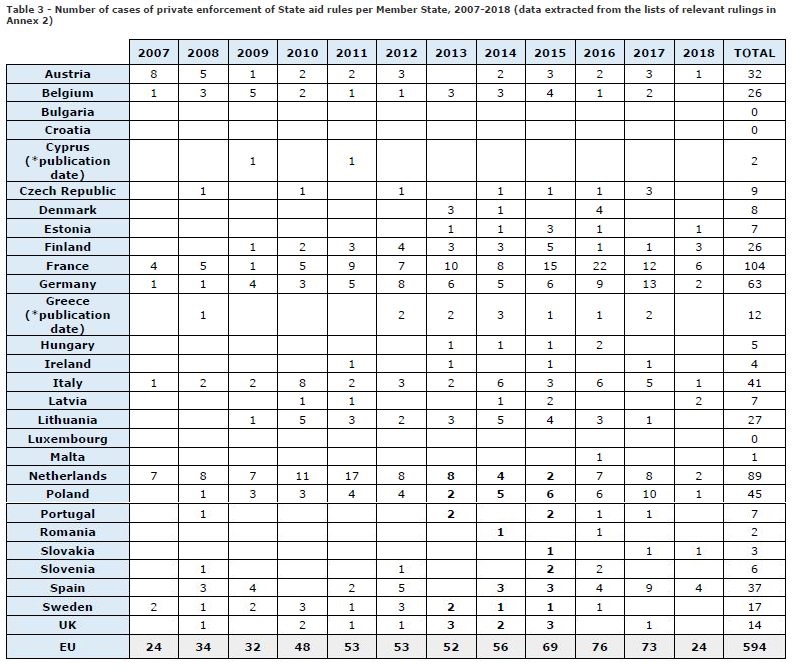

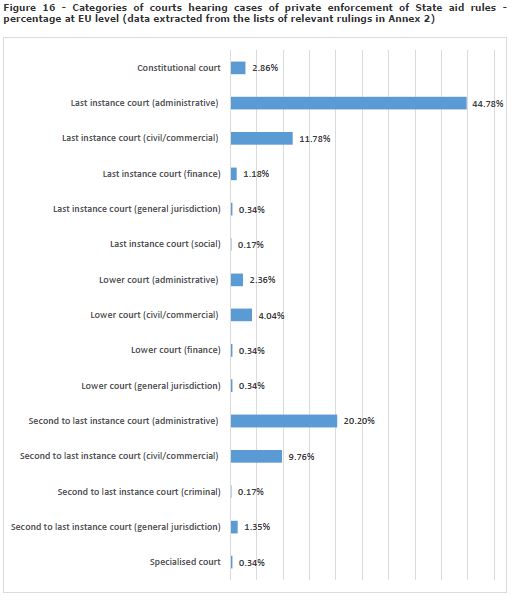

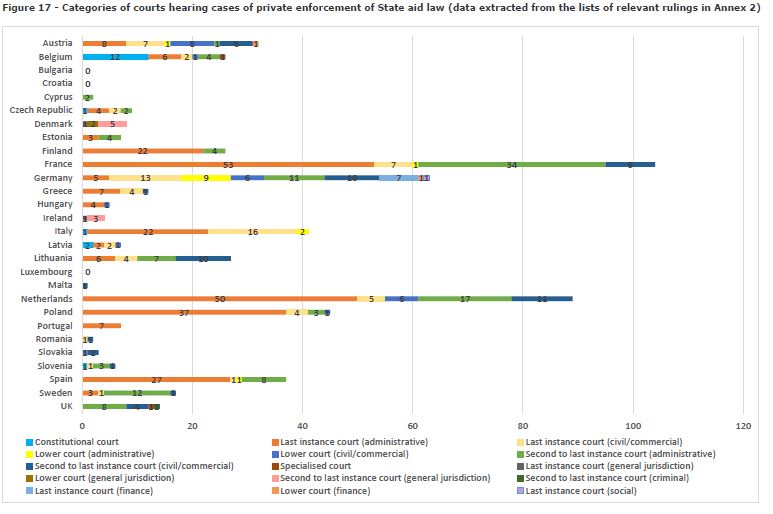

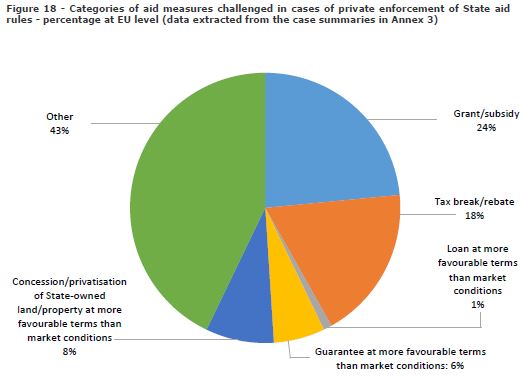

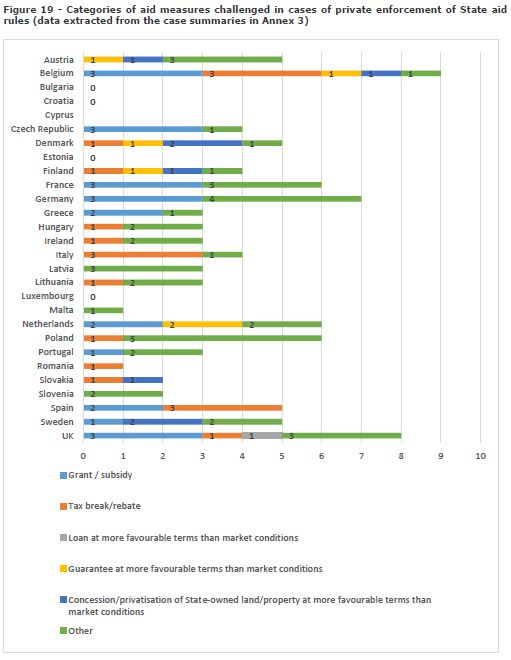

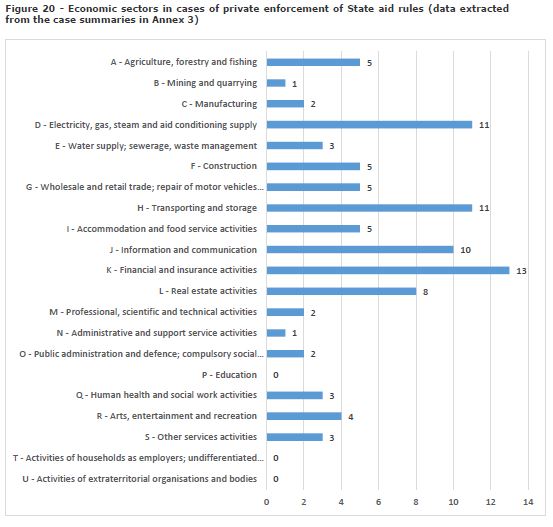

The first trend identified in Chapter 2 concerns the overall increase in the number of judgments handed down by national courts during the period covered by the Study. A second trend concerns the increase in private enforcement cases, which have exceeded the number of public enforcement rulings. The Consortium has identified 172 cases of public enforcement of State aid rules and 594 private enforcement cases, thus making the number of private enforcement cases more than triple the number of public enforcement cases. The increase in the number and size of State aid measures put in place by Member States in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis may have contributed to the substantial increase in the number of private enforcement cases in the first half of the 2010s.

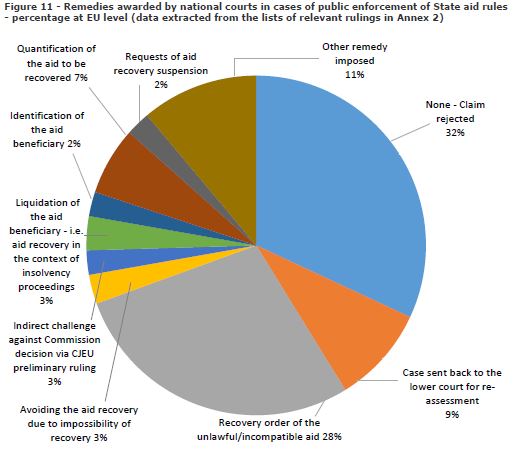

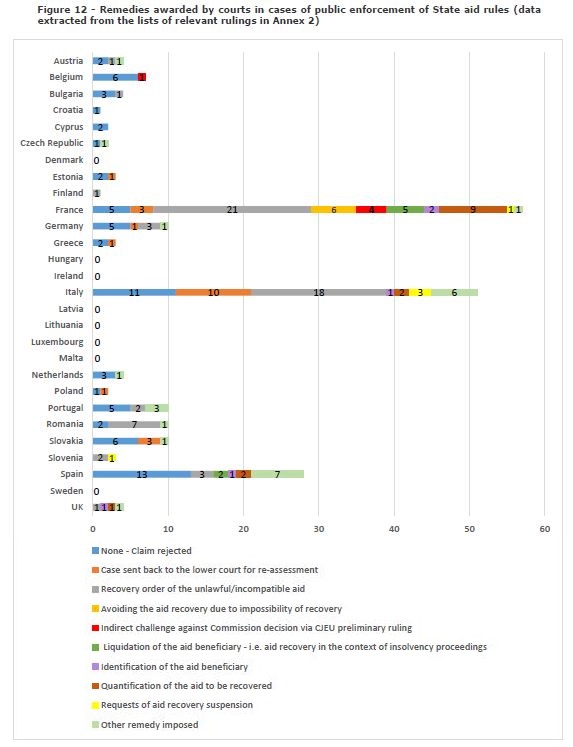

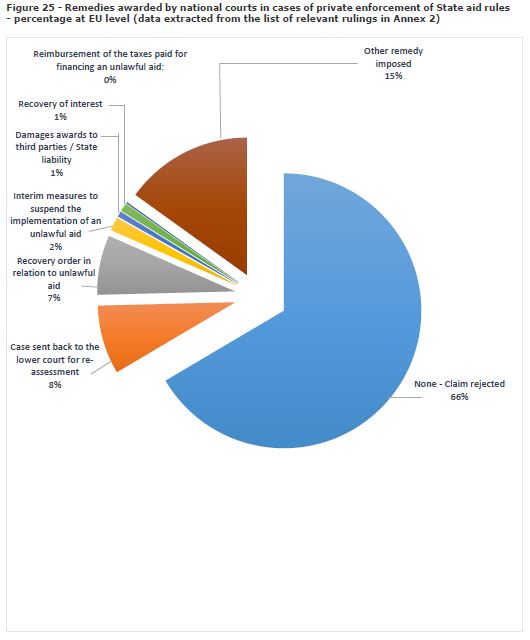

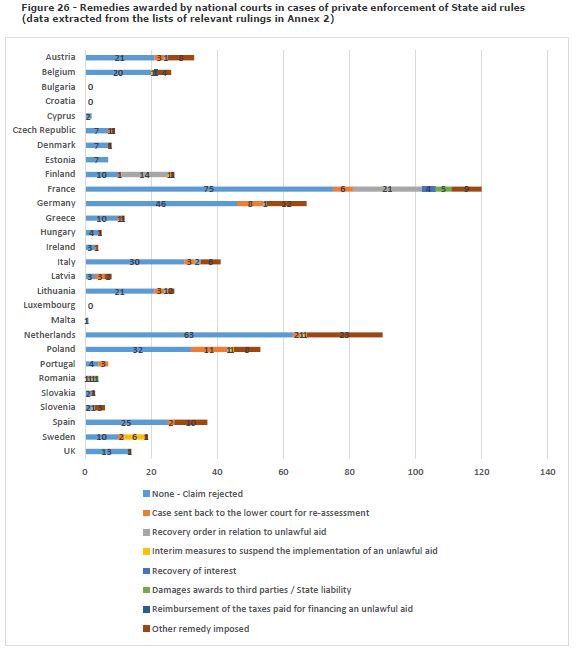

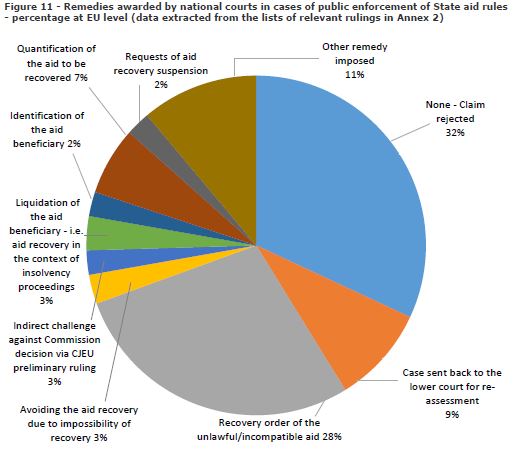

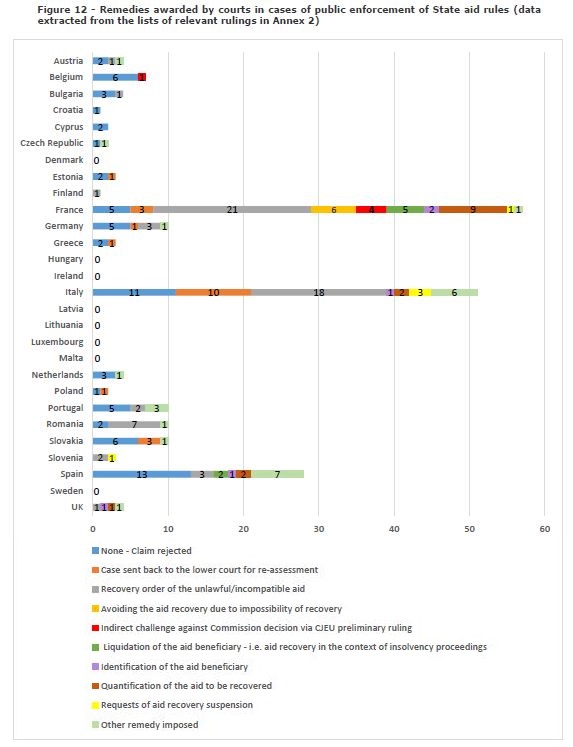

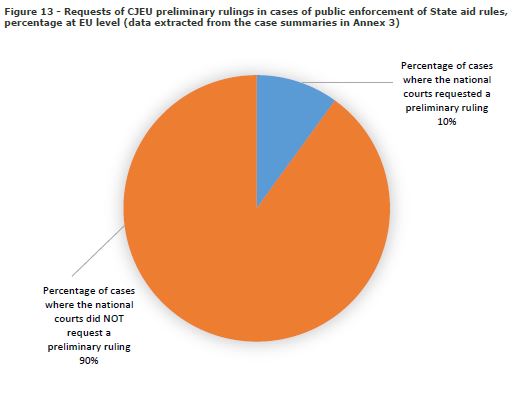

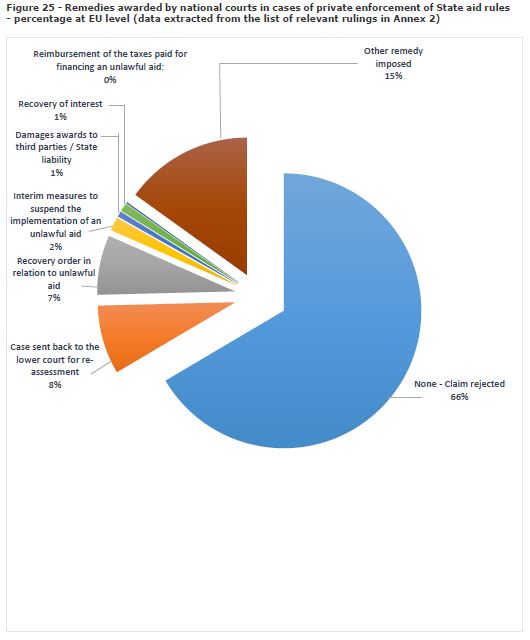

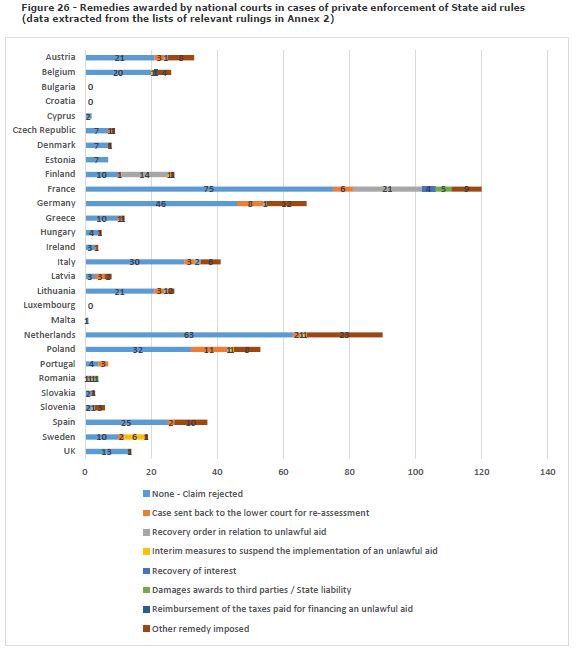

Despite the increase of court litigation, national courts have rarely concluded that unlawful aid has been granted and hence rarely awarded remedies. In 32% of the identified cases of public enforcement and in 66% of the identified cases of private enforcement, the national court rejected the claim. In public enforcement, this can be considered as a positive trend: it shows that national recovery orders are rarely successfully challenged in national courts. In particular, it is worth noting that only in five cases did the national courts adopt interim measures to suspend the enforcement of the recovery order (i.e. 2% of the public enforcement cases identified in the Study). Consequently, it appears that Commission decisions are enforced by national authorities without facing the risk of lengthy national litigation, which might delay the effective aid recovery.

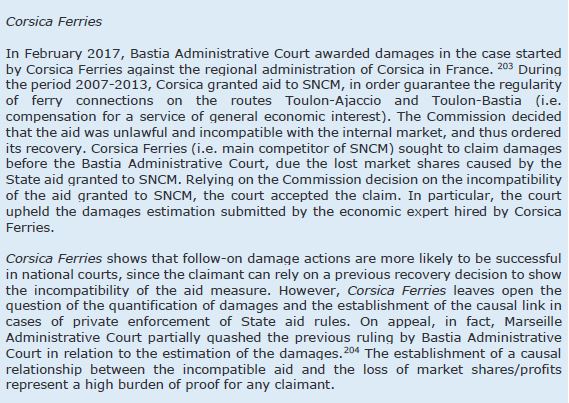

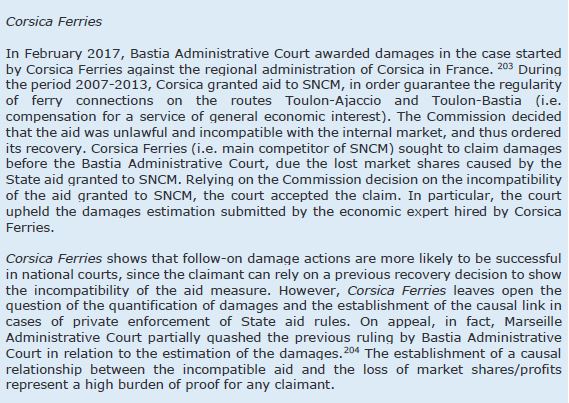

On the other hand, the low number of remedies awarded by national courts in the identified private enforcement cases calls for further reflection. National courts rarely either order the recovery of the unlawful aid or adopt interim measures to suspend the implementation of the aid measure. This trend is particularly evident in relation to damages claims: only in six of the identified relevant rulings did national courts award compensation due to the harm caused by a breach of the standstill obligation by a Member State (i.e. less than 1% of the private enforcement cases identified in the Study). The country reports reveal a number of reasons which may explain why national courts rarely award remedies in private enforcement cases. Firstly, besides the lack of familiarity with State aid rules among national courts, a number of national legal experts report that the claimants do not usually put forward well-structured arguments to support their claims. Secondly, it appears that national courts face difficulties in verifying the conditions concerning the notion of aid under Article 107(1) TFEU, under the GBER, as well as applying the CJEU case law in relation to Altmark and Market Economic Operator Principle (MEOP). Thirdly, a number of national reports stress that State aid claims often require national courts to assess the legality of the measure under different areas of law (e.g. tax, administrative, contract law); the interaction of different legal regimes makes the evaluation of the measure under State aid rules more complex. Fourthly, a number of national reports point out that national courts are often reluctant to order the recovery of the unlawful aid while the case is awaiting a compatibility assessment by the Commission. Finally, a State aid claim generally implies a rather high burden of proof for the claimant, especially in damages claims. In the latter category of cases, the plaintiff must prove that the challenged measure represents an unlawful aid not previously notified to the Commission and that the aid measure caused damage to the claimant. The breach of the standstill obligation may cause either a loss of profits and/or a loss of market share for the competitors of the aid beneficiary. In both cases, it can be quite challenging for the claimant to estimate the damage suffered during the entire period that the unlawful aid was in operation. In fact, exogenous factors may have an impact on the profits and market share of the claimant.

The increased familiarity of national judges with State aid rules may improve via the organisation of training programmes and advocacy activities organised by the Commission and national authorities. On the other hand, the number of successful damages claims might increase if national courts were to receive ‘further guidance’ in relation to the economic techniques concerning damages estimation in State aid cases. In this regard, it is worth noting that in 2013 the Commission published a Practical Guide, summarising the economic techniques concerning damages estimation in cases of private enforcement of EU competition rules. This Practical Guide is a non-binding document, which specifically targets national courts and explains to national judges the steps followed by economists to quantify damages in a EU competition law cases in simple and accessible language. National judges increasingly rely on the Practical Guide, which is considered a useful framework to assess the reliability of the damage estimation put forward by the experts hired by the parties. The Consortium considers that such guidance can be seen as a positive example. It might even be contended that, if applied to State aid enforcement, it might increase the number of successful damages claims in national courts, thus supporting a growth in the number of cases of private enforcement of State aid rules.

Best Practices in State aid enforcement

The trends identified in Chapter 2 suggest that State aid enforcement at national level is becoming more effective in most Member States. The best practices presented in Chapter 3 reveal that certain Member States are aware that amending national procedures may be vital to making State aid enforcement more effective. Many of these practices are designed to embed a ‘culture’ of enforcement of State aid rules among the national stakeholders (i.e. granting authorities, beneficiaries and third parties).

The Consortium has based its indicators for best practices on the information gathered from the country reports and case summaries identified in this Study. The best practices that the Consortium has subsequently discerned mainly concern national procedural rules and judicial practices which can contribute to reducing the length of the aid recovery proceedings after a Commission decision. In particular, the Consortium has identified seven best practices, divided in three categories:

- Best practices related to recovery: specific legislation, recovery instructions in State aid instruments and national penalties for delays in recovery;

- Best practices concerning national screening mechanisms: ex-ante (i.e. non-binding compatibility assessment with State aid rules) and ex-post mechanisms (i.e. State aid assessment as part of the decision-making process of the administrative authority);

- Best institutional practices: rules clarifying the court jurisdiction in State aid disputes and the principle of investigation, according to which a court must ascertain the facts of the case on its own initiative and provide the parties with an explanation about the proceedings and the legal formalities.

In recent years, a number of Member States have adopted specific legal frameworks governing aid recovery. Although these laws broadly differ in terms of scope of application, administrative authorities involved and procedural steps in the recovery process, they represent a best practice in relation to the enforcement of State aid rules at the national level. The adoption of a specific legal framework may increase legal certainty and reduce court litigation, thus ensuring the effective enforcement of recovery decisions. Further best practices identified in relation to aid recovery are the inclusion of instructions about possible recovery proceedings in the administrative act granting the aid, as well as the adoption of internal penalties to sanction the national authorities if they do not enforce the Commission decision in a proper and timely manner. The latter best practice complements the financial penalties that the CJEU could impose on a Member State in the context of infringement proceedings, due to the lack of enforcement of a recovery decision.

Additionally, the Consortium considers the screening mechanisms introduced in a number of Member States as a best practice. Such mechanisms could work either ex-ante (i.e. a national authority provides a non-binding compatibility assessment to the granting authority, thus anticipating the likely Commission assessment of the aid measure before its notification) or ex-post (i.e. a national authority monitors the compatibility of aid measures already implemented with GBER, de minimis Regulation and the concept of aid, and it can eventually order the recovery of the unlawful aid without a Commission decision). The legality of the ex-post system of control has been recently confirmed by the CJEU in Eesti Pagar, And is in line with the increased relevance of the GBER since State Aid Modernisation. Finally, it is worth pointing out that the ex-ante mechanisms are based on non-binding opinions delivered by national authorities to the granting institution concerning the likely compatibility of the planned aid measure with State aid rules; such non-binding opinions do not replace the Commission’s exclusive competence in carrying out the compatibility assessment under Article 107(2) and 107(3) TFEU and under the provisions adopted pursuant to Articles 93, 106(2), 108(2) and 108(4) TFEU.

At the institutional level, the Study points out as best practices the rules clarifying the jurisdiction of the courts in State aid disputes, as well as the principle of investigation in court proceedings. While the former best practice makes national judges more familiar with State aid rules, the latter aims at supporting the plaintiff in developing a claim in line with the remedies available under State aid rules, thus increasing the number of successful claims in national courts.

While the abovementioned best practices may provide helpful lessons, the principle of national procedural autonomy militates against some of them becoming more generally widespread. On the other hand, a number of the best practices simply create working practices that make State aid monitoring and enforcement smoother, and thus can easily be replicated in different Member States. In other words, the best practices identified in the present Study mostly concern judicial practices that could be easily applied by national courts, rather than requiring legislative intervention. Since the beginning of State Aid Modernisation, the Commission has set up a number of working groups bringing together representatives from both the Member States and the Commission, in order to discuss issues related to State aid enforcement. The Commission could thus establish a working group to facilitate the exchange of best practices among the Member States’ representatives. Within such a working group, the Member States could assist each other, in order to either refine existing policies (i.e. for the Member States that already apply one of the best practices) or in considering how far these practices could improve State aid enforcement in their country (i.e. for Member States that do not have such practices).

Use of the cooperation tools by the Commission and the national courts

Based on the data gathered and the analysis presented in Chapter 4, the Consortium provides a number of key observations, and conclusions on the use of and views on the cooperation tools provided for in Article 29 of the State aid Procedural Regulation. The tools included in Article 29 are the request for information; the request for opinion; and amicus curiae observations.

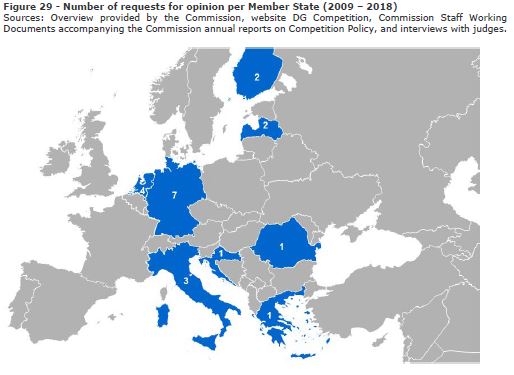

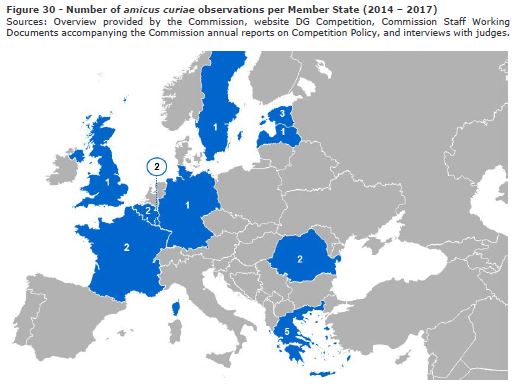

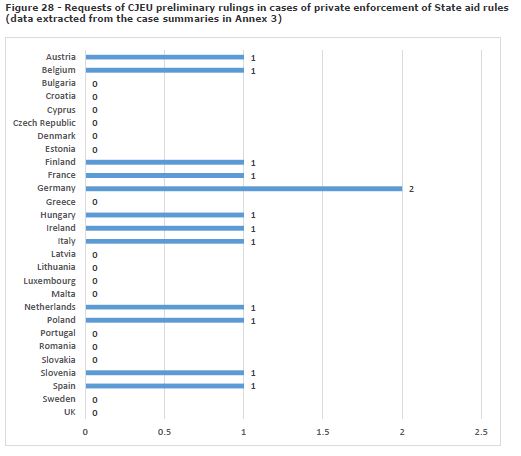

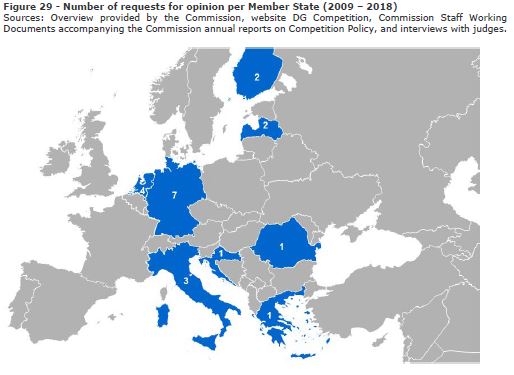

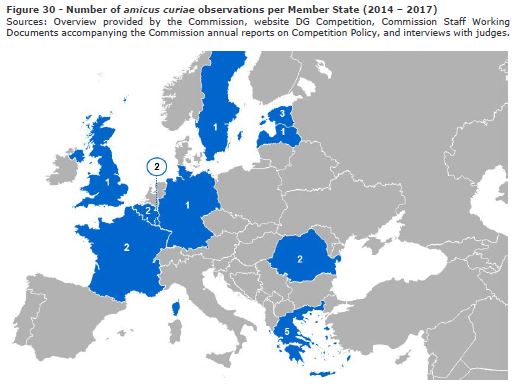

National courts seem to rely on the cooperation tools on a moderate scale. In the Study Period, the Commission received at least seven requests for information. In that same period, the Commission provided at least 20 amicus curiae observations. Information on the requests for opinion is available since 2009. The Commission provided at least 21 opinions at the request of national courts since that year.

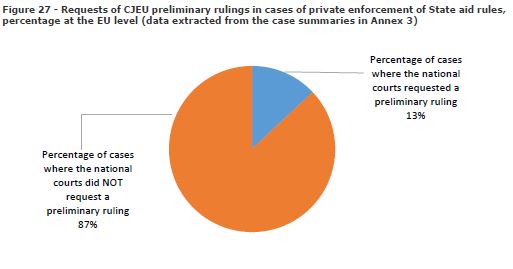

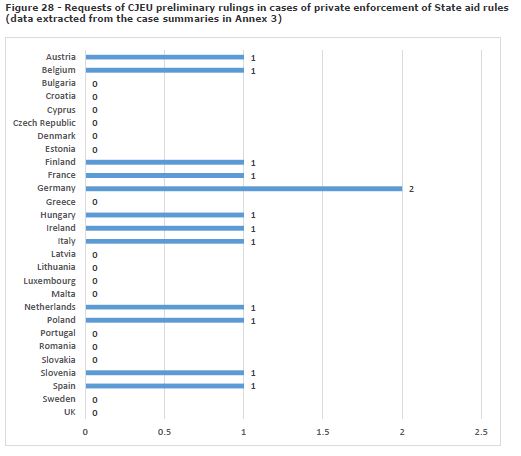

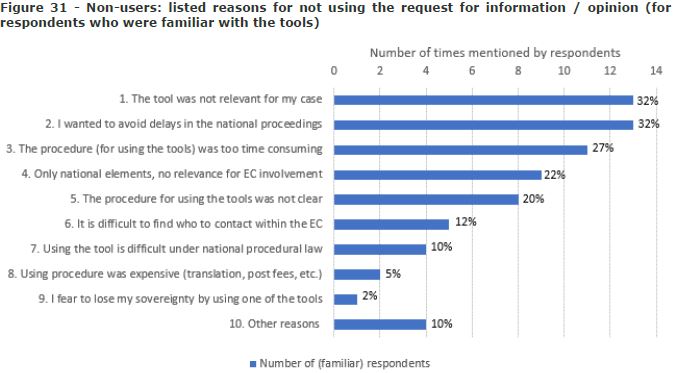

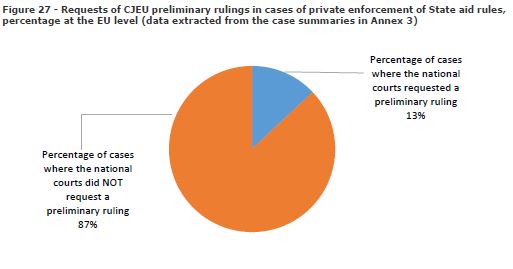

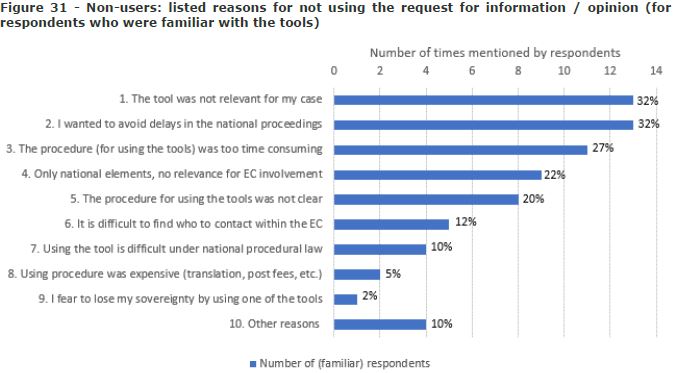

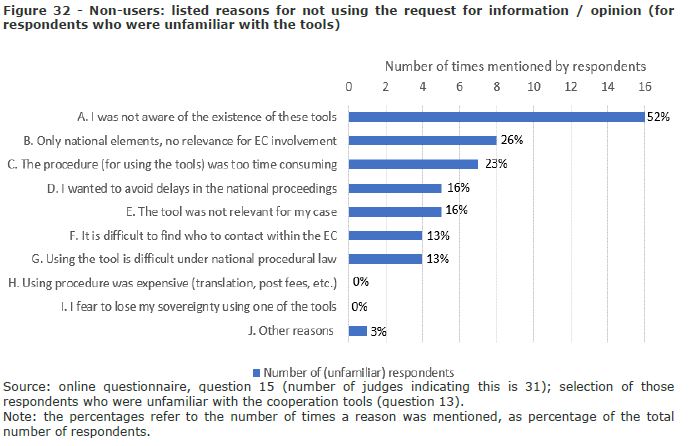

The Consortium has identified two main reasons for the limited use of cooperation tools. First of all, seeking guidance from the Commission regarding State aid-related questions does not seem to be the most likely approach for judges to take. The vast majority of judges prefer to invest time and effort themselves to try to find an answer to the (legal) question at hand. Consultation with fellow judges at the same court is the second most likely action. Furthermore, if the judge cannot find the answer to (legal) question at hand, judges are more likely to seek advice from the CJEU through a request for a preliminary ruling than to approach the Commission.

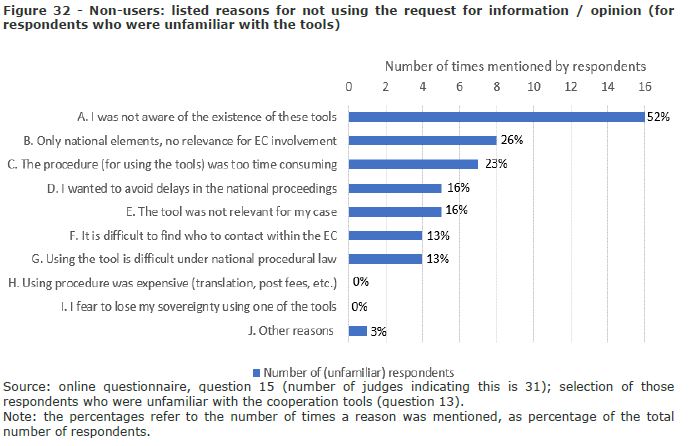

A second reason for the limited use of cooperation tools seems to relate to a lack of awareness of the existence of the cooperation tools among judges. Around 40% of judges participating in the online questionnaire indicated that they had not heard of any of the cooperation tools before participating in the Study. The judges interviewed confirmed this finding. Several of them also indicated that their fellow judges were not familiar with the tools’ existence. Even judges who are aware of some of the tools, are often not familiar with all of them. This lack of awareness among judges on the existence of cooperation tools may be addressed by initiatives to raise awareness among judges.

Although seeking advice from the Commission does not seem to be the obvious route for judges to take, judges do value the possibility of approaching the Commission. Moreover, the willingness to use the cooperation tools in future cases seems considerable among judges. Feedback from judges who had made use of the cooperation tools, showed that the possibility to communicate in the national language is highly valued by the judges. With regard to the quality of the Commission’s responses, in particular the usefulness of the response in the ongoing court case, judges differ in opinion. Some judges indicated being quite satisfied with the information, while a minority indicated that they did not consider the information obtained to be very helpful. With regard to the procedure, the majority of judges are of the opinion that the procedure is easy and effective. Nevertheless, it does not always seem to be clear to judges which procedure they have to follow.

The main potential endeavours that the Commission could undertake to support the use of cooperation tools include:

- Improving (the accessibility of) practical guidance on the cooperation tools procedures. Potential places where this information would be made available could be, in addition to the website of the Commission (DG Competition), locations that judges typically use for finding legal information, such as the EUR-Lex-website.

- The dissemination of information on and promotion of both State aid rules in general and the cooperation tools in particular, with the aim of increasing overall awareness among national judges. To achieve this, the Commission could introduce an online platform, which offers the opportunity for a judge to look up the required information as well as to ask a question online on a protected platform only accessible by judges.

Introduction

Ce document comprend l’étude finale de « L’Etude sur l’application des règles et l’exécution des décisions en matière d’aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales (COMP/2018/001) » (ci-après « l’étude »), réalisée pour la DG Concurrence de la Commission Européenne (ci-après « la Commission ») par Spark Legal Network (ci-après « l’équipe de collecte des données »), l’Institut universitaire européen (ci-après « l’équipe des aides d’Etat ») ; Spark Legal Network et l’Institut universitaire européen étant ci-après désignés ensemble : « le groupe d’étude »), Ecorys (« l’équipe des outils de coopération ») et Caselex (« l’équipe éditoriale ») (tous ensemble désignés ci-après par « le consortium »). Le consortium a eu l’appui d’un réseau d’experts juridiques nationaux qui étaient en charge de la collecte des données juridiques et de l’analyse de l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat au niveau national, en soumettant des résumés des affaires ainsi que des rapports par pays.

L’étude comprend quatre chapitres. Le chapitre 1 traite du contexte juridique, des objectifs et de la méthodologie adoptée dans le cadre de l’étude. Le chapitre 2 présente un résumé et une analyse de l’application des aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales dans toute l’Union européenne (ci-après « UE »), en décelant les principales tendances concernant l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales. Le chapitre 3 fournit une liste de bonnes pratiques en matière d’application d’aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales de l’UE. Le chapitre 4 est axé autour des conclusions tirées de l’analyse de l’utilisation des outils de coopération par la Commission et les juridictions nationales dans le cadre des affaires liées à des aides d’Etat. L’étude comprend quatre annexes qui détaillent davantage la méthodologie et les résultats liés à la collecte des données.

Le contexte juridique

Selon l’article 107(1) du traité sur le fonctionnement de l’Union européenne (ci-après « TFUE »), les aides d’Etat accordées par les Etats membres sont interdites. Selon l’article 108(3) TFUE, les Etats membres sont dans l’obligation de notifier à la Commission tout projet d’autorisation d’une nouvelle aide qui respecterait les conditions énumérées à l’article 107(1) TFUE. De plus, les Etats membres de l’UE (ci-après « Etats membres ») doivent respecter une obligation de statu quo selon laquelle ils ne peuvent mettre en œuvre une mesure d’aide avant que la Commission n’ait achevé son évaluation de la compatibilité de l’aide notifiée. La Commission est exclusivement compétente pour connaître de la question de savoir si l’aide en l’espèce est interdite selon l’article 107(1) TFUE ou si elle peut être considérée comme compatible avec le marché intérieur.

Selon l’article 263(1) TFUE, la Cour de Justice de l’Union européenne (ci-après « CJUE ») a une compétence exclusive en matière d’examen de la légalité des décisions de la Commission. Par conséquent, les juridictions nationales des Etats membres ne peuvent examiner les décisions de la Commission en matière d’aides d’Etat. Toutefois, ces juridictions nationales sont impliquées dans l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat dans le cadre de deux types de procédure :

- L’exécution des décisions de restitution (dans le cadre de l’application publique des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat) : une fois que la Commission a adopté une décision de restitution (en enjoignant à un Etat membre de restituer l’aide incompatible qui a été adoptée précédemment en violation de l’obligation de statu quo), les juridictions nationales seront impliquées dans la procédure de restitution.

- L’application de l’article 108(3) TFUE (dans le cadre de l’application privée des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat) : les tiers intéressés peuvent entamer une action devant une juridiction nationale compte tenu de l’effet direct de l’obligation de statu quo de l’article 108(3) TFUE. Les concurrents du bénéficiaire de l´aide peuvent notamment demander la restitution de l’aide mise à exécution en violation de l’obligation de statu quo (dite l’aide illégale), indépendamment de l’évaluation de compatibilité réalisée par la Commission. Finalement, les concurrents peuvent introduire des actions en dommages et intérêts. Dans le cadre de l´application privée, les juridictions nationales statuent sur le fait de savoir si la mesure contestée remplit les conditions pour constituer une aide d´Etat conformément à l´article 107(1) TFUE, c’est-à-dire si elle constitue une aide illégale en raison d´une absence de notification à la Commission.

Objectifs et méthodologie

L’objectif de l’étude était de présenter un état des lieux de l’application des aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales de l’UE. De ce fait, l’étude offre un aperçu global de l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales des 28 Etats membres, en identifiant des nouveaux enjeux et tendances ainsi qu’en présentant des bonnes pratiques. L’étude examine les affaires nationales concernant l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat, qui ont été jugées entre le 1er janvier 2007 et le 31 décembre 2017 et elle inclut des affaires importantes décidées en 2019 (ci-après « la période d’étude »). En outre, l’étude offre un aperçu de l’utilisation des outils de coopération par la Commission et les juridictions nationales. Afin de répondre aux objectifs de l’étude, les tâches suivantes ont été menées :

- Tâche 1 : identifier, classifier et résumer les décisions les plus pertinentes rendues par les juridictions nationales en matière d’aides d’Etat ;

- Tâche 2 : un résumé des principales conclusions au niveau de l’UE ;

- Tâche 3 : L’identification de bonnes pratiques ;

- Tâche 4 : L’utilisation des outils de coopération par la Commission et les juridictions nationales

Au cours de la Tâche 1, le groupe d’étude, en coopération avec les experts juridiques nationaux, a identifié et a compilé une liste des décisions pertinentes rendues par les juridictions nationales des Etats membres au cours de la période d’étude (la liste complète des décisions pertinentes se trouve à l’annexe 2). Ces décisions émanent de l’ensemble des Etats membres à l’exception d’un seul (à savoir le Luxembourg). A partir de la liste des décisions pertinentes, l’équipe d’étude et les experts juridiques nationaux ont sélectionné un échantillon de décisions au niveau des Etats membres et de l’UE sur la base de leur pertinence juridique, et de leur caractère novateur (« décisions sélectionnées »). De façon subséquente, les experts juridiques nationaux ont rédigé les résumés des affaires pour les décisions sélectionnées, sur base d’un modèle créé par l’équipe d’étude. Ils ont également rédigé les rapports par pays pour chaque Etat membre, en se basant également sur un modèle, en fournissant des conclusions générales sur l’état des lieux concernant les règles en matière d’aides d’Etat au niveau national (les rapports par pays, les décisions sélectionnées ainsi que les rapports des affaires peuvent être trouvés à l’annexe 3). De plus, au cours de la mise en œuvre de la tâche 1, l’équipe éditoriale a créé un site internet du projet ainsi qu’une base de données de la jurisprudence. Le site internet du projet est accessible au public et contient les résultats présentés dans l’étude finale, tout comme la base de données de la jurisprudence. Ces derniers seront maintenus accessibles pour deux ans au moins après la fin de l´étude. La base de données de la jurisprudence comprend 145 rapports des affaires rédigés dans le cadre de la présente étude et elle offre aux visiteurs une panoplie d’options de recherche afin de trouver et de lire les rapports des affaires de façon conviviale.

L’exécution de la tâche 1 a servi de base pour les tâches 2 et 3. Ces dernières ont été réalisées par l’équipe d’étude (avec l’appui de l’équipe de collecte des données). La tâche 2 consiste en l’analyse et le résumé des principales conclusions au regard de l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales de l’UE, en se basant notamment sur une liste de 766 décisions pertinentes, de 145 rapports des affaires et de 28 rapports par pays produits sous la tâche 1. L’analyse a porté tant sur l’application publique que privé des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat et a consisté en l’élaboration d’un certain nombre de statistiques, en l’identification d’un nombre de tendances qualitatives ainsi qu’en la comparaison avec des recherches antérieures pertinentes. L’objectif de la tâche 3 a été d’identifier un nombre de bonnes pratiques dans le cadre de l’application des aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales des Etats membres. Afin d’identifier ces bonnes pratiques, l’équipe des aides d’Etat a créé un ensemble d’indicateurs afin d’évaluer la manière selon laquelle une juridiction donnée réagit : a) la rapidité avec laquelle les affaires pouvant être résolues du fait de la pratique utilisée ; b) la qualité de la coordination avec des procédures parallèles de la Commission ; c) le degré selon lequel les réparations accordées constituent une indemnité adéquate ; et d) les outils utilisés pour le dialogue judiciaire. Dans le cadre de cette évaluation, l’équipe des aides d’Etat ne s’est pas contentée d’étudier la pratique, mais s’est également penchée sur le contexte dans lequel la pratique s’exerce (encore appelé « cadre judiciaire national pertinent »).

L’objectif de la tâche 4, effectuée par l’équipe des outils de coopération, a été de mener une recherche, en rassemblant les connaissances sur l’utilisation et les points de vue sur les outils de coopération énumérés à l’article 29 du règlement de la procédure sur les aides d’Etat. Afin de réaliser les objectifs de recherche de la tâche 4, différentes méthodes de collecte des données ont été employées : recherche documentaire (en utilisant des données à disposition des services de la Commission), entretiens avec le personnel de la Commission, un questionnaire en ligne à l’attention des juges des juridictions pertinentes (105 répondants, dont 78 ont été pertinents pour l’étude), ainsi que les entretiens avec différents juges de l’UE (27 entretiens).

L’application des aides d’Etat par les juridictions nationales

Dans le chapitre 2, le consortium identifie un nombre de tendance concernant l’application publique et privée des règles en matière d’aide d’Etat par les juridictions nationales des Etats membres. Alors que l’application publique se réfère à des litiges dans des juridictions nationales concernant l’obligation de restitution, l’application privée se réfère à un litige devant les juridictions émanant des violations de l’obligation de statu quo de l’article 108(3) TFUE.

La première tendance identifiée dans le chapitre 2 est relative à l’augmentation générale du nombre de décisions rendues par les juridictions nationales au cours de la période faisant l’objet de la présente étude. Une deuxième tendance décelée, concerne l’augmentation des dossiers d’application privée qui ont dépassé le nombre de décisions d’application publique. Le consortium a identifié 172 affaires d’application publique des aides d’Etat et 594 affaires d’application privée, le nombre des affaires d’application privée correspond donc à trois fois le nombre des cas d’application publique. L’augmentation du nombre et de la taille des mesures des aides d’Etat mises en place par les Etats membres au lendemain de la crise financière de 2008 a pu avoir contribué à l’augmentation substantielle du nombre d’affaires d’application privée au cours de la première moitié des années 2010.

Malgré l’augmentation des procédures devant les juridictions, les juridictions nationales ont rarement statué qu´une aide illégale a été attribuée. Par conséquent, elles ont rarement accordé des réparations. Dans 32% des affaires d’application publique identifiées et dans 66% des affaires d’application privée identifiées, les juridictions ont rejeté la demande. En matière d’application publique, cela peut être analysé comme une tendance : en effet, les obligations de restitution nationale réussissent rarement à être contesté devant les juridictions nationales. Il est important de noter que seuls dans cinq affaires les juridictions nationales adoptent des mesures provisoires afin de suspendre l’application de l’obligation de restitution (plus précisément dans 2% des affaires d’application publique identifiées dans l´étude). Par conséquent, les décisions de la Commission sont appliquées par les juridictions nationales sans courir le risque de procédures longues au niveau national qui sont susceptibles de différer la restitution effective de l’aide.

Toutefois, le nombre très faible de réparations accordées par les juridictions nationales dans les cas d’application privée appelle à la réflexion. Les juridictions nationales ordonnent rarement la restitution des aides illégales ou adoptent des mesures provisoires pour suspendre la mise en œuvre des mesures d’aides. Cette tendance est particulièrement manifeste dans le cadre des actions en dommages et intérêts : seules dans six des décisions pertinentes identifiées, les juridictions nationales ont octroyé une indemnisation en raison du préjudice causé par la violation de l’obligation du statu quo par un Etat membre (donc dans 1% des affaires d’application privée identifiées dans l´étude). Les rapports par pays révèlent un certain nombre d´éléments qui pourraient expliquer la raison pour laquelle les juridictions nationales n´accordent que rarement des réparations dans les affaires d´application privée. Premièrement, outre l´absence de familiarité des juridictions nationales avec les règles en matière d´aides d´Etat, un certain nombre d´experts juridiques nationaux constatent que les demandeurs ne mettent pas toujours en place un argumentaire structuré pour étayer leur requête. Deuxièmement, il semble que les juridictions nationales font face à des difficultés dans la vérification des conditions appliquées à la notion d´aide conformément à l´article 107(1) TFUE, au règlement général d’exemption par catégorie, à la jurisprudence de la CJUE relative à l´arrêt Altmark ainsi qu´au principe dit de l'investisseur en économie de marché. Troisièmement, un certain nombre de rapports par pays soulignent que les actions en matière d´aides d´Etat requièrent souvent que les juridictions nationales apprécient la légalité de la mesure sous l´angle de différents domaines du droit (par exemple le droit fiscal, le droit administratif, le droit des obligations) ; cette interaction entre différents régimes juridiques complexifie le processus d´évaluation de la mesure sous l´angle des règles en matière d´aides d´Etat. Quatrièmement, un certain nombre de rapports par pays soulignent que les juridictions nationales sont souvent réticentes à ordonner la restitution de l´aide illégale alors que l´affaire est sous l´évaluation de compatibilité dans le chef de la Commission. Finalement, une action en matière d’aides d’Etat implique généralement une lourde charge de la preuve pour le plaignant, surtout en matière d’action en dommages et intérêts. Dans ce dernier cas, le plaignant doit prouver que la mesure en cause représente une aide illégale qui n’a pas été précédemment notifiée à la Commission, et que la mesure d’aide lui a causé un dommage. La violation de l’obligation de statu quo a causé soit une perte de profit et/ou un recul de la part de marché du concurrent du bénéficiaire de l’aide. Dans les deux cas, il peut s’avérer difficile pour le plaignant d’estimer le préjudice subi pendant la période au cours de laquelle l´aide illégale était en vigueur. En effet, des facteurs exogènes ont pu avoir un impact sur ses bénéfices et ses parts de marchés.

La croissante familiarité des juges nationaux avec les règles d’aides d’Etat pourrait s’améliorer à travers la mise en place de programmes de formation et des activités de promotion organisés par la Commission et les autorités nationales. Toutefois, le nombre d’actions en dommages et intérêts accueillies favorablement peuvent augmenter si les juridictions nationales reçoivent « davantage d’indications » en matière de techniques économiques concernant la quantification du préjudice dans les affaires en matière d’aides d’Etat. A cet effet, il est important de noter qu’en 2013, la Commission a publié un Guide Pratique qui résume les techniques économiques concernant la quantification du préjudice dans les affaires d’application privée des règles de la concurrence de l’UE. Le Guide Pratique est un document non contraignant qui cible particulièrement les juridictions nationales et explique aux juges nationaux les étapes suivies par les économistes afin de quantifier le préjudice dans une affaire de droit de la concurrence de l’UE dans un langage simple et accessible. Les juges nationaux s’appuient de plus en plus sur le Guide Pratique qui est considéré comme cadre utile d’évaluation de la fiabilité de la quantification du préjudice mise en avant par les experts engagés par les parties au litige. Le consortium considère que ce guide peut être considéré comme un exemple positif. Il pourrait même être affirmé que, si appliqué à au régime des aides d´Etat, ce guide pourrait augmenter le nombre d´actions en dommages et intérêts qui aboutiraient devant les juridictions nationales, et ainsi contribuer à l´accroissement des affaires d´application privée des règles en matière d´aides d´Etat.

Les bonnes pratiques en matière d’application des aides d’Etat

Les tendances identifiées dans le chapitre 2 suggèrent que l’application des aides d’Etat au niveau national devient de plus en plus effective dans la plupart des Etats membres. Les bonnes pratiques présentées au Chapitre 3 révèlent que certains Etats membres ont conscience qu’amender les procédures nationales est vital pour l’effectivité de l’application des aides d’Etat. Nombreuses de ces pratiques ont pour but d’amorcer une « culture » de l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat parmi les acteurs nationaux (à savoir les autorités qui accordent les subventions, les bénéficiaires et les tiers).

Le consortium a placé ses indicateurs pour les bonnes pratiques en fonction des informations recueillies à partir des rapports par pays et des rapports des affaires identifiées dans la présente étude. Les bonnes pratiques qui ont été décelées par le consortium concerne principalement les règles procédurales nationales et les pratiques juridiques qui pourraient contribuer à réduire la longueur des procédures en matière de restitution des aides après la décision de la Commission. Le consortium a identifié notamment sept bonnes pratiques, divisées en trois catégories :

- Bonnes pratiques en relation avec la restitution : une législation spécifique, des directives en matière de restitution dans le cadre des outils en matière des aides d’Etat et les sanctions pénales pour tout retard dans la restitution ;

- Les bonnes pratiques qui concernent les mécanismes nationaux de filtrage ex ante (à savoir une évaluation de compatibilité non contraignante avec les aides en matière d´aides d´Etat) et les mécanismes ex post (à savoir une évaluation des aides d´Etat en tant que faisant partie du processus décisionnel de l´autorité administrative) ;

- Les bonnes pratiques dites institutionnelles : les règles clarifiant la compétence juridictionnelle dans le cadre de litiges en matière d´aides d´Etat et le principe de l’investigation, selon lesquels une juridiction doit, de sa propre initiative, vérifier les faits de l´espèce et fournir aux parties une explication concernant les procédures et les formalités juridiques à suivre.

Depuis quelques années, certains Etats membres ont adopté une cadre légal spécifique gouvernant la restitution des aides. Malgré le fait que ces lois divergent grandement en termes de champ d’application, d´autorités administratives impliquées et d´étapes procédurales dans le processus de restitution, elles constituent une bonne pratique dans le cadre de l’application des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat au niveau national. L’adoption d’un cadre juridique spécifique pourrait accroître la sécurité juridique et réduire les procédures judiciaires, donc assurer l’application effective des décisions de restitution. D’autres bonnes pratiques identifiées dans le cadre de la restitution des aides sont l’inclusion des instructions concernant des potentielles procédures de restitution dans les actes administratifs octroyant les aides, ainsi que l’adoption de sanctions internes afin de sanctionner les autorités nationales si elles n’appliquent pas la décision de la Commission de manière ponctuelle et adéquate. Cette dernière bonne pratique complète les sanctions financières que la CJUE pourrait imposer à un Etat membre dans le cadre d’une procédure en manquement du fait de l’absence de l’application de toute décision de restitution.

En outre, le consortium considère les mécanismes de filtrage introduits par certains Etats membres comme bonne pratique. De tels mécanismes pourraient être employés soit de manière ex-ante (lorsqu’une autorité nationale fournit une évaluation de compatibilité non contraignante à l’autorité qui accorde la subvention et anticipe ainsi avant toute notification, l’évaluation probable de la mesure d’aides par la Commission), soit de manière ex post (lorsque l’autorité nationale contrôle la compatibilité des mesures d’aides mises en œuvres avec le règlement général d’exemption par catégorie, le règlement de minimis, ainsi qu´avec la notion d’aide, et pourrait ordonner la restitution de l’aide illégale sans décision de la Commission). La légalité du système de contrôle ex post a d’ailleurs été récemment confirmée par la CJUE dans l´arrêt Eesti Pagar, et est conforme avec la croissante pertinence du règlement général d’exemption par catégorie depuis la modernisation du contrôle des aides d´Etat. Finalement, il est important de souligner que les mécanismes ex ante se fondent sur des avis non contraignants des autorités nationales aux autorités accordant l´aide et qui se réfèrent à la potentielle compatibilité de l´aide planifiée avec les règles en matière d´aides d´Etat ; ces avis non contraignants ne se substituent pas à la compétence exclusive de la Commission dans la mise en œuvre de l´évaluation de compatibilité prévue aux articles 107(02) et 107(3) TFUE ainsi que dans les dispositions adoptées en vertu des articles 93, 106(2), 108(2) et 108(4) TFUE.

Au niveau institutionnel, l’étude analyse comme bonne pratique les règles clarifiant les compétences des juridictions dans les litiges en matière d´aides d ´Etat, ainsi que le principe d’investigation dans les procédures juridictionnelles. Alors que la première bonne pratique rend les juges nationaux plus familiers avec les règles des aides d’Etat, la dernière aide a pour objectif d’assister le plaignant dans la mise en place de sa demande conforme aux réparations disponibles dans le cadre des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat, et ainsi augmenter le nombre de réussite des demandes devant les juridictions nationales.

Alors que les bonnes pratiques mentionnées ci-dessus pourraient fournir des enseignements utiles, le principe d’autonomie procédurale nationale milite contre leur expansion généralisée. Toutefois, un nombre de bonnes pratiques créent tout simplement des pratiques de travail qui facilitent la surveillance et l´application des aides d´Etat, et peuvent ainsi aisément être reproduites dans d´autres Etats membres. En d’autres termes, les bonnes pratiques identifiées dans l´étude portent principalement sur les pratiques juridictionnelles qui pourraient aisément être appliquées par les juridictions nationales, plutôt que de favoriser une intervention législative. Depuis le début de la modernisation du contrôle des aides d´Etat, la Commission a établi un certain nombre de groupes de travail qui réunissent des représentants des Etats membres et de la Commission afin de discuter des questions relatives à l´application des aides d´Etat. Par conséquent, la Commission pourrait établir un groupe de travail dans le but de faciliter l´échange de bonnes pratiques entre les représentants des Etats membres. Au sein d´un tel groupe de travail, les Etats membres pourraient s’assister mutuellement afin d’améliorer des politiques existantes (pour les Etats membres qui appliquent déjà les bonnes pratiques) ou d’analyser dans quelle mesure ces pratiques pourraient améliorer l’application des aides d’Etat dans leurs pays (pour les Etats membres qui n´ont pas adopté de telles pratiques).

L’utilisation des outils de coopération par la Commission et les juridictions nationales

Sur base des données recueillies et l’analyse présentée dans le Chapitre 4, le consortium fournit un nombre d’observations clé et de conclusions sur l’utilisation et des points de vue sur les outils de coopération tels que définis à l’article 29 du règlement procédural sur les aides d’Etat. Les outils inclus dans l’article 29 sont la demande de renseignement, la demande d’avis, et les observations de l’amicus curiae.

Les juridictions nationales semblent recourir aux outils de coopération de façon modérée. Au cours de la période d’étude, la Commission a reçu au moins sept demandes de renseignement. Au cours de la même période, la Commission a fourni au moins vingt amicus curiae. La Commission a fourni au moins 21 avis à la demande des juridictions nationales depuis 2009, date à laquelle toute information relative aux demandes d’avis a été rendue disponible.

Le consortium a identifié deux raisons principales pour l´utilisation limitée des outils de coopération. Premièrement, demander conseil à la Commission concernant des questions relatives aux aides d’Etat ne semble pas être l’approche favorisée par les juges. La plus grande majorité des juges préfère consacrer eux-mêmes du temps et de l’effort afin d´essayer de trouver une réponse à la question (juridique) d´espèce. Ensuite, consulter leurs collègues de la même juridiction est la deuxième approche employée. Finalement, si le juge ne peut trouver de réponse à la question (juridique) d´espèce, les juges s´adresseront plus probablement à la CJUE à travers une demande de décision préjudicielle plutôt qu´à la Commission.

Une seconde raison qui explique l’utilisation limitée des outils de coopération semble être relative à une absence de prise de conscience parmi les juges de l’existence des outils de coopération. En effet, environ 40% des juges ayant participé au questionnaire en ligne ont indiqué qu’ils n’ont jamais entendu parler des outils de coopération avant d’avoir participé à la présente étude. Les juges interviewés ont confirmé cela : certains ont indiqué que leurs collègues n’étaient pas familiers avec l’existence de ces outils. D’ailleurs, même les juges qui ont connaissances de certains des outils, ne sont pas nécessairement familiers avec l’ensemble des outils. Il pourrait être remédié à ce manque de connaissance parmi les juges sur l’existence des outils de coopération grâce à des initiatives de sensibilisation.

Même si demander l’avis de la Commission ne semble pas être l’approche la plus courante adoptée par les juges, les juges apprécient la possibilité de s’adresser à la Commission. De plus, la volonté d’utiliser les outils de coopération par les juges dans de futures affaires semble importante. Les retours obtenus des juges qui ont utilisé les outils de coopération ont montré que la possibilité pour eux de communiquer dans leur langue nationale est largement valorisée. Au regard des questions relatives à la qualité des réponses de la Commission, et notamment l’utilité des réponses dans le cadre d’affaires en cours, les avis des juges divergent. Certains juges indiquent être satisfaits avec les renseignements obtenus, alors qu’une minorité d’entre eux considère que les renseignements obtenus n’étaient pas utiles. Quant à la procédure, la majorité des juges sont d’avis qu’elle est facile et efficace. Toutefois, il ne semble pas toujours être clair pour eux quelle procédure ils doivent suivre.

Les principales initiatives que la Commission pourrait engagées pour soutenir l’utilisation des outils de coopération sont les suivantes :

- Améliorer l’accessibilité sur les directives pratiques concernant les procédures en matière d’outils de coopération. Ces informations pourraient être mises à disposition, outre sur le site internet de la Commission (DG Concurrence), également sur les plateformes régulièrement utilisées par les juges pour rechercher des informations juridiques, comme par exemple le site internet d’EUR-Lex.

- La diffusion de l’information et la promotion des règles en matière d’aides d’Etat en général et des outils de coopération en particulier, en ayant comme objectif l’augmentation de la prise de conscience générale des juges nationaux. Pour atteindre cet objectif, la Commission pourrait mettre en place une plateforme en ligne qui permettrait à un juge de vérifier l´information requise et de poser une question en ligne sur une plateforme protégée uniquement accessible aux juges.

1. Context and objectives of the Study

This document constitutes the Final Study for the ‘Study on the enforcement of State aid rules and decisions by national courts (COMP/2018/001)’ (also referred to as: the ‘Study’), carried out for DG Competition of the European Commission (also referred to as: the ‘Commission’) by Spark Legal Network (also referred to as: the ‘Data Collection Team’), the European University Institute (also referred to as: the ‘State Aid Team’; Spark Legal Network and the European University Institute are together also referred to as: the ‘Study Team’), Ecorys (also referred to as: the ‘Cooperation Tools Team’) and Caselex (also referred to as: the ‘Editorial Team’) (together also referred to as: the ‘Consortium’). The Consortium was supported by a network of national legal experts who were responsible for legal data collection and analysis on the enforcement of State aid rules at national level, producing case summaries and country reports.

This Final Study starts with an introductory chapter (the current Chapter 1) which includes the legal context, the objectives and a summary of the methodology applied throughout the Study. Chapter 2 presents a summary and analysis of State aid enforcement by national courts across the European Union (also referred to as: the ‘EU’), comprising the main trends with regard to the enforcement of EU State aid rules by national courts across the EU. Chapter 3 provides best practices in State aid enforcement by national courts across the EU. Chapter 4 focuses on the findings with regard to the use of cooperation tools by Commission and national courts in relation to State aid rules.

The following annexes are attached to this Study:

- Annex 1: Technical details: Detailed methodology and supporting materials.

- Annex 2: List of relevant rulings on State aid matters: Covering 27 Member States , contained in a spreadsheet.

- Annex 3: Country reports: Each of the 28 country reports contains general conclusions on the state of play of State aid rules at national level, a list of the relevant rulings rendered by the Member State's courts, and summaries of a selected sample of rulings (also referred to as: ‘selected rulings’).

- Annex 4: Methods and evidence of data collection for Task 4 (on the use of cooperation tools by the Commission and national courts).

1.2 Introduction to EU State aid rules

1.2.1. Introduction to EU State aid rules

Under Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

(also referred to as: the 'TFEU'), State aid granted by Member States of the

European Union (also referred to as: 'Member States') is prohibited. However,

aid is or may be considered compatible with the internal market under Article

107(2) and (3), and under the provisions adopted pursuant to Articles 93,

106(2), 108(2) and 108(4) TFEU.

Under Article 107(1) TFEU, a State measure is considered 'State aid' when

the following cumulative conditions are met:

- The aid is granted to either one or a group of 'undertakings' - i.e.

any public support granted to individuals is outside the scope of State

aid control. An undertaking is broadly defined by the case law of the

Court of Justice of the European Union (also referred to as: the 'CJEU')

as "any entity engaged in an economic activity regardless of the legal

status of the entity and the way in which it is financed”.

- The aid is granted "by a Member State or through State resources”. The

aid, therefore, can be granted by central, regional or local State authorities,

as well as by State-owned undertakings.

- The aid is "selective' – i.e. the aid is discriminatory, and thus only a

single/limited number of products and/or undertakings within the internal

market benefit from the aid.

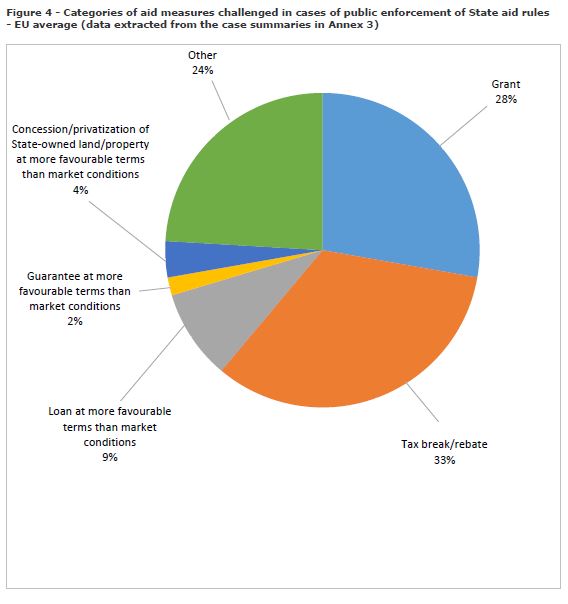

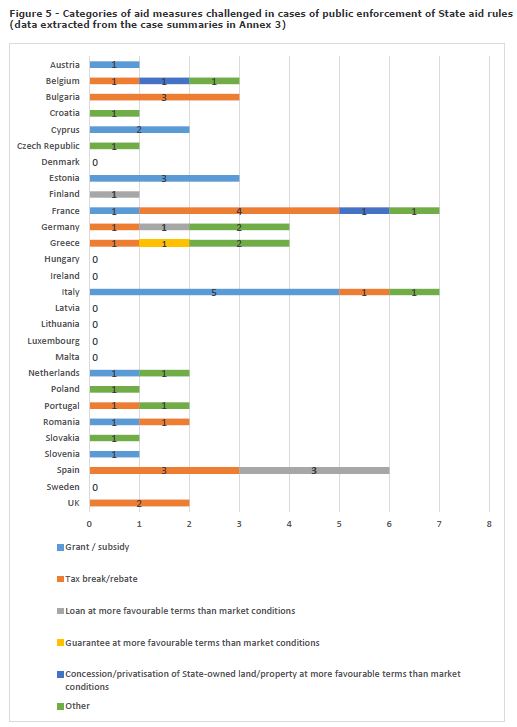

- The aid creates an 'advantage' for the beneficiary undertaking. The aid can

take "any form" – i.e. a grant, tax rebate, loan/State guarantee at an interest

rate more favourable than under market conditions. When the existence of an

advantage is not self-evident, like in the case of a loan or State guarantee,

the advantage will be assessed on the basis of the 'Market Economic Operator

Principle' (MEOP). The test follows this logic: would a market operator grant

a loan/State guarantee to the beneficiary undertaking at the same conditions

as the Member State? If the answer is positive, there is no State aid, since

the State in such case acts like a market economic operator.

- The aid "affects trade between Member States”. The condition has been

broadly interpreted by CJEU case law to include any aid that could

potentially/indirectly affect trade between Member States.

- The aid "distorts or threatens to distort competition” in the internal

market. This condition is usually presumed to be satisfied when the

previous cumulative conditions are fulfilled.

Under Article 108(3) TFEU, Member States must notify to the Commission any

plan to grant new aid that fulfils the conditions under Article 107(1) TFEU.

In addition, Member States are subject to a standstill obligation, whereby

they cannot implement the aid measure before the Commission has completed

the compatibility assessment of the notified aid. The Commission, in fact,

has the exclusive competence to assess whether aid prohibited under Article

107(1) TFEU is or may be considered compatible with the internal market under

Article 107(2) and (3) and under the provisions adopted pursuant to Articles

93, 106(2), 108(2) and 108(4) TFEU.

Under Article 263(1) TFEU, the CJEU has exclusive jurisdiction to review the

legality of Commission decisions. Therefore, national courts of the Member

States cannot review the Commission State aid decisions. However, according

to the 2009 Commission Notice on the enforcement of State aid rules by national

courts (also referred to as: the '2009 Enforcement Notice'), national courts

are involved in the enforcement of State aid rules in relation to two types

of legal proceedings:

- Implementation of recovery decisions (i.e. public enforcement of State aid

rules): once the Commission adopts a recovery decision (ordering a Member

State to recover incompatible aid previously implemented in breach of the

standstill obligation), the national courts will be involved in the recovery

proceedings.

- Enforcement of Article 108(3) TFEU (i.e. private enforcement of State aid

rules): interested third parties can start an action in a national court

in view of the direct effect of the standstill obligation under Article

108(3) TFEU. In particular, competitors can ask for the recovery of the

aid implemented in breach of the standstill obligation (i.e. unlawful aid),

independently of the compatibility assessment carried out by the Commission.

Finally, competitors can also start damages actions. In the context of private

enforcement, national courts rule on whether the challenged measure fulfils

the conditions to be considered State aid under Article 107(1) TFEU and

thus it represents unlawful aid, having not been notified to the Commission.

The present Study covers both public and private enforcement of State aid rules

by national courts of the Member States.

1.2.2. Public enforcement of State aid rules

When the Commission adopts a recovery decision, the Member State concerned ""...shall

take all the necessary measures to recover the aid from the beneficiary." The aid

beneficiary may try to avoid the implementation of the recovery decision by

challenging the recovery order or any other implementing act adopted by the

national authorities, before a national court. In particular, national courts

fulfil a number of functions in the context of the implementation of the

recovery decision:

- Quantification of the State aid to be recovered: The Commission is not

required to quantify the exact amount of the aid to be recovered in

its decision. The latter is a task usually left to national authorities.

Recovery shall cover the time from the date when the aid was put at the

disposal of the beneficiary until the moment of the effective recovery.

The amount to be recovered shall bear interest until the moment of the

effective recovery. Courts may be called upon to adjudicate on any

resulting dispute between the beneficiaries and the State in relation

to same.

- Identification of the aid beneficiary: National authorities may have

to identify the aid beneficiary. This might be a complex task in case

the beneficiary had been either acquired by another firm or split into

different firms. Similarly, the national authorities need to identify

both the direct and indirect aid beneficiaries from whom the aid should

be recovered. Here too, litigation in a national court is possible if

there is a dispute as to the identification of the beneficiary.

- Suspension of the recovery procedure: National courts do not have jurisdiction

to review the legality of the Commission decision. In addition, challenging

the decision before the General Court of the European Union (also referred

to as the 'GC') and the CJEU does not have a suspensory effect under Article

278 TFEU. Nevertheless, in Atlanta and Zuckerfabrik, the CJEU ruled that a

national court can order the suspension of the recovery decision in exceptional

circumstances. In particular, in these rulings the CJEU identified four

cumulative conditions to justify the suspension by a national court of the

implementation of the recovery decision:

- The national court has "serious doubts" about the validity of the Commission

decision. The national court should refer a request for a preliminary ruling

to the CJEU, unless the Commission decision has already been challenged

before the CJEU.

- "There is urgency, in that the interim relief is necessary to avoid serious

and irreparable damage being caused to the party seeking the relief."

- The national court takes "due account of the interest of the EU".

- The national court must "respect the CJEU case law".

- Indirect challenges against a Commission decision: Member States can directly

challenge the legality of the Commission decisions as 'privileged actors' under

Article 263(4) TFEU. In accordance with the Plaumann test, the aid beneficiary

can challenge the Commission decision under Article 263(4) second limb if they

are individually concerned by a decision "by reason of certain attributes which

are peculiar to them or by reason of circumstance in which they are differentiated

from all other persons”. By contrast, competitors rarely fulfil the conditions

under Article 263(4) second limb to have legal standing in accordance with the

Plaumann test. The CJEU has recently 'softened' the conditions of legal standing

of the competitors of the aid beneficiary in Montessori. In the judgment, the

CJEU interpreted the meaning of Article 263(4) third limb in the field of State

aid rules. The provision, introduced by the Lisbon Treaty, grants to natural and

legal persons the locus standi to challenge at the GC "…a regulatory act which

is of direct concern to them and does not entail implementing measures”.

In Montessori, the CJEU recognised that Commission State aid decisions are,

subject to certain conditions, 'regulatory acts' Therefore, competitors will

be able in the future to rely on this recent case law to challenge Commission

decisions.

In addition, in view of the traditional restrictive wording of

the Plaumann test and in order to guarantee judicial redress to the aid beneficiary,

in Atzeni the CJEU recognised that in case the plaintiff does not fulfil the conditions

of locus standi under Article 263(4) second limb TFEU, it could indirectly challenge

the legality of the Commission decision before a national court. In line with Atlanta

and Zuckerfabrik case law, in such case the national court would refer a request for

a preliminary ruling to the CJEU in relation to the legality of the recovery decision.

However, in view of the recent Montessori ruling, Atzeni case law may become less

relevant: competitors may rely on the Montessori ruling to claim legal standing at

the GC.

- Aid recovery in the context of insolvency proceedings: An alternative to full recovery

of the unlawful/incompatible aid is the liquidation of the beneficiary. Insolvency

procedures are carried out in accordance with national law. However, the CJEU has

elaborated a number of general principles that should guide national courts in

insolvency procedures involving the recovery of incompatible/unlawful aid:

- The beneficiary's assets should be sold in an open and transparent manner.

- The insolvency procedure must lead to the cessation of business activities of

the aid beneficiary.

- In the context of the insolvency procedures, the State aid claim should be

registered on the basis of the appropriate ranking.

- National courts must ensure that there is no economic continuity with the

successor company. The successor company is liable to pay back the aid only

if there is economic continuity with the aid recipient. Unless the original

beneficiary paid back the full amount of the aid, in fact, that amount should

be registered in the schedule of liabilities and recovered in the context of

the insolvency procedures.

- Assessing the impossibility to recover the aid: As mentioned above, the insolvency

of the aid beneficiary is not a justification to avoid the implementation of the

recovery decision. According to the CJEU case law, recovery can be avoided only

when it is "absolutely impossible”. Nevertheless, "political and legal difficulties”

faced by Member States in the context of the recovery procedure do not represent a

valid justification to avoid the implementation of the Commission decision.

- Assessing the recovery time limit: in view of the principle of legal certainty, the

State aid Procedural Regulation defines a time limit of 10 years for the recovery of

unlawful aid. Such time limit is counted from the moment the unlawful aid is granted

to the beneficiary; the time limit is interrupted if the Commission opens investigations

concerning the unlawful aid. Therefore, national courts might be called on to assess

claims concerning the impossibility of aid recovery put forward by the beneficiary

concerning the expiry of the 10 years' time limit.

In terms of the applicable EU acquis, the national courts will primarily be guided by

the recovery decision concerning the individual unlawful/incompatible aid which they must

enforce at the national level. Secondly, national courts will be guided by CJEU case law,

defining their tasks in relation to public enforcement of State aid rules. Finally, the

national courts may also refer to the Commission Recovery Notice.

From a procedural point of view, on the other hand, recovery takes place "… in accordance

with the procedures under the national law of the Member State concerned” (i.e. principle of

procedural autonomy). In particular, the courts that have jurisdiction to hear disputes

concerning recovery orders implementing a Commission decision can vary from country to country.

However, on the basis of the principles of equivalence and effectiveness, national procedural

rules cannot undermine the effective enforcement of the recovery decision.

1.2.3. Private enforcement of State aid rules

Under Article 108(3) TFEU, Member States cannot implement an aid measure before its final

approval by the Commission (i.e. standstill obligation). In SFEI, the CJEU recognised the

horizontal direct effect of Article 108(3) – i.e. any affected party can request before a

national court the recovery of the aid disbursed in breach of the standstill obligation

(i.e. unlawful aid).

As mentioned above, national courts cannot assess the compatibility of the aid.

Nevertheless, national courts must assess whether a State measure qualifies as 'State aid',

and thus determine if it was implemented unlawfully. In particular, national courts check

if the aid fulfils:

- The cumulative conditions under Article 107(1) TFEU: In this regard, the national

court will have to take into consideration the CJEU case law on Article 107(1) TFEU,

as codified by the 2016 Commission Notice on the Notion of State aid.

- The General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER): Aid schemes that fulfil the GBER

conditions are presumed to be compatible, and thus they do not need to be notified

to the Commission. National courts are empowered to assess the compliance of State

aid measures with the GBER.

- The State aid de minimis Regulation: Under the de minimis Regulation, aid measures

below EUR 200,000 granted during a period of three fiscal years are considered to be

"too small” to have a distortive impact on the competition in the internal market

under Article 107(1) TFEU, and thus they do not need to be notified to the Commission.

Such threshold is increased to EUR 500,000 in relation to de minimis aid granted in

the context of Services of General Economic Interest (SGEI).

- ‘Existing aid': State aid measures granted by a Member State before joining the

EU or previously approved by the Commission are considered existing aid. Under

Article 108(1) TFEU, the Commission, in cooperation with the Member States, constantly

monitors existing aid. In particular, the Commission can ask for the modification of

the aid measure if the conditions in the market have changed, and thus the measure

is not needed anymore. On the other hand, existing aid measures are not unlawful

and thus they cannot be subject to private enforcement claims in national courts.

National courts, therefore, may verify if a measure qualifies as 'existing aid',

but the Commission has exclusive competence to ask for modifications/abolition of

the aid measure in view of new developments in the market.

Besides ordering the recovery of the unlawful aid, national courts can adopt interim

measures to suspend the implementation of unlawful aid (e.g. ordering the granting

authority to suspend the implementation of unlawful aid). The objective of the interim

injunction is to protect the rights of the claimant during the court proceedings.

In order to guarantee the effective recovery of the unlawful aid, the national court

should also order the recovery of the interest earned by the beneficiary. In other words,

the recovery should not be limited to the nominal value of the aid, but it should also

cover the financial advantage that the beneficiary gained from the aid. The recovery of

interest aims at forfeiting the time advantage enjoyed by the aid beneficiary. The

'advantage' is equivalent to the difference between what the aid beneficiary could

have obtained in the market and the cost of its financing under the aid measure concerned.

The interest accrues from the moment the aid was at the disposal of the beneficiary until

the effective recovery of the aid. National courts will rely on national rules on the

calculation of the applicable interest rate. However, due to the principles of

equivalence and effectiveness, the application of national rules should not lead to

the calculation of a lower interest rate in comparison to the rate calculated by the

Commission in similar circumstances. Finally, as ruled by the CJEU in CELF, the

recovery of the interest is independent from the compatibility assessment; recovery

of the interest should always take place even if the unlawful aid has been declared

compatible by the Commission.

Besides the recovery of the interest, in SFEI the CJEU recognised that the competitors

of the beneficiary can be entitled to receive compensation due to the damage caused by

the unlawful aid. Such compensation should be paid by the granting institution, rather

than by the beneficiary, since the latter is not liable for the lack of compliance with

the notification obligation. The notification to the Commission is, in fact, an obligation

that falls entirely on the national authorities. Therefore, the conditions for obtain

damages for a breach of State aid rules are the equivalent to State liability for breach

of Union law. In Francovich, the CJEU recognised for the first time that Member States

may be liable to pay compensation to individuals due to the damage caused by the lack

of implementation of an EU Directive. In Brasserie du Pêcheur, the CJEU introduced

general criteria to assess Member State liability for breach of Union law: the breached

Union law should confer rights on individuals; there is "serious breach” of Union law;

there is a "causal link” between the breach and the damage suffered by the plaintiff.

With regard to State aid rules, the standstill obligation under Article 108(3) TFEU

grants rights to individuals and lack of compliance by a Member State is considered a

"serious breach” of Union law. The major challenge faced by the plaintiff is represented

by the damage quantification and by showing the existence of a causal link between the

damage suffered and the lack of compliance with the standstill obligation. Finally,

competitors might receive compensation from the aid beneficiary if this type of action

is allowed under national law.

The last type of remedy involving private enforcement of State aid rules concerns

tax measures imposed by Member States to finance an unlawful State aid measure. In

Streekgewest, the CJEU recognised that a third party can challenge its tax burden

when the tax payment "forms an integral part of the unlawful State aid measure”.

In particular, the claimant can challenge the unlawful aid even if it is not a competitor

of the aid beneficiary, and thus even if it is not directly affected by the unlawful aid.

On the contrary, a third party cannot obtain from a national court an exemption from

the payment of a tax which is equivalent to the unlawful aid. Such exemption, in fact,

would broaden the number of beneficiaries of the unlawful aid, rather than reduce it.

Such exemption could be granted under national non-discrimination and unfair

competition law.

The EU acquis does not harmonise the national procedural rules followed by national

courts. In accordance with the principle of procedural autonomy, in fact, national

rules define which courts have jurisdiction in recovery proceedings and damages

claims, as well as the procedural rules which are applicable. However, in view

of the principle of equivalence and effectiveness, national courts could set aside

certain national procedural rules that make the enforcement of State aid rules de

facto impossible. The following table summarises the relevant EU acquis and types

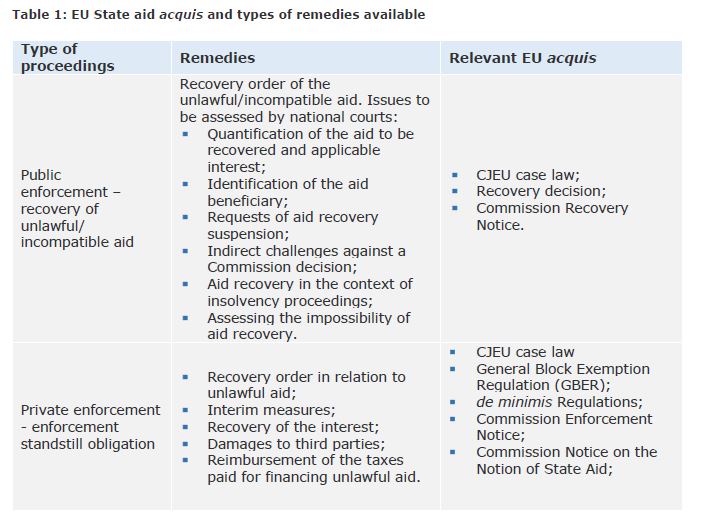

of remedies available in relation to the two types of enforcement proceedings.

1.3. Objectives of the Study

The aim of this Study is to provide the state of play of State aid enforcement

by national courts in the EU. It therefore offers a comprehensive overview of

the enforcement of State aid rules by national courts of the 28 Member States,

identifying emerging trends and challenges, and presenting best practices.

The Study looks at national enforcement cases which were decided between 1 January 2007

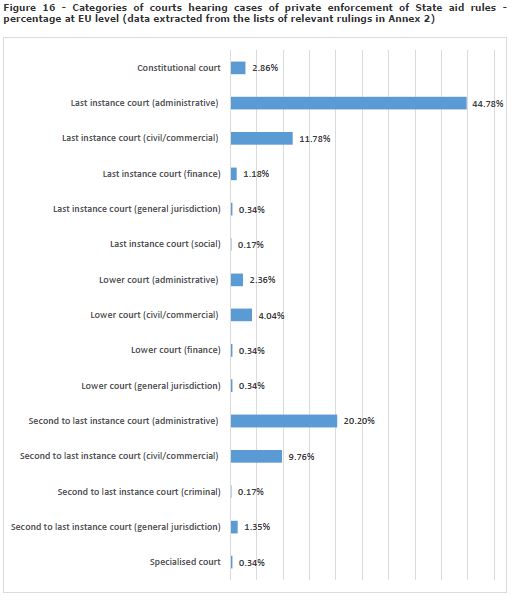

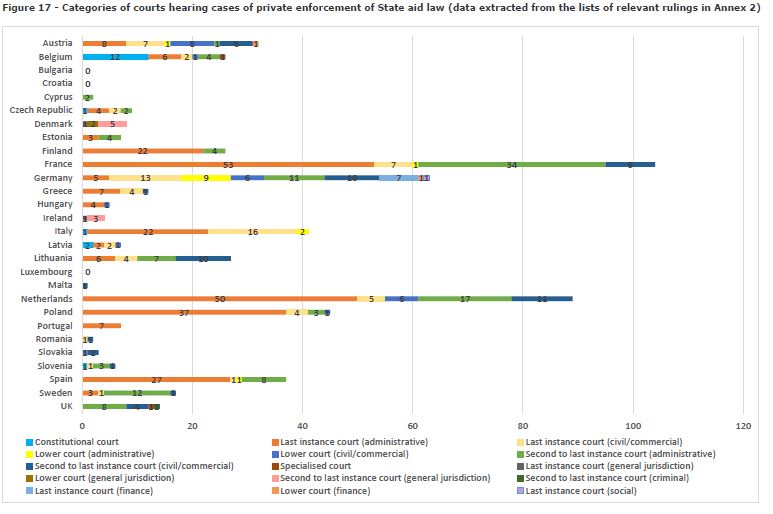

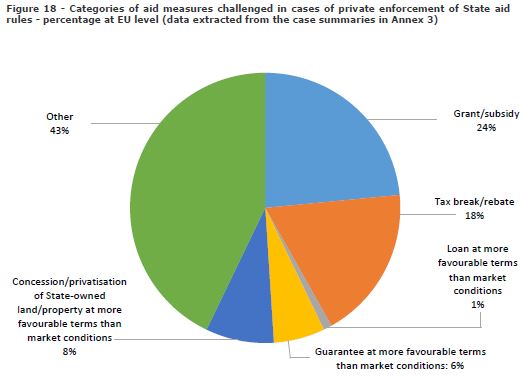

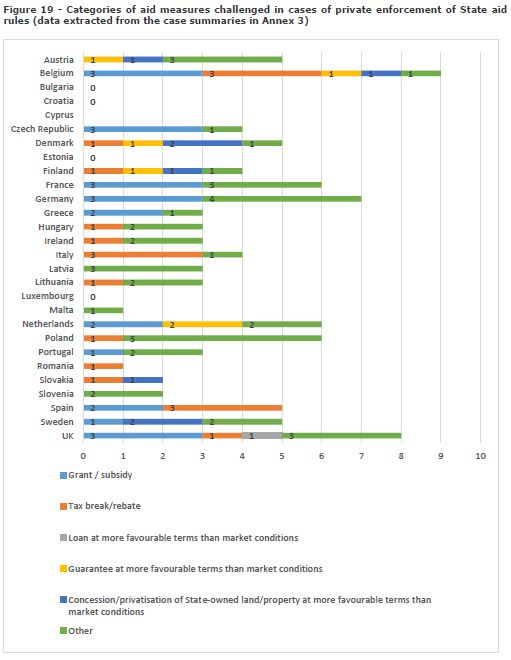

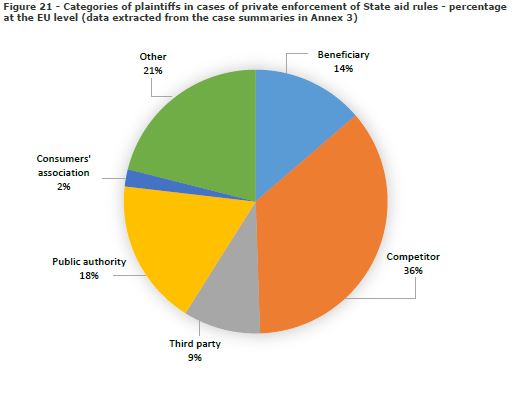

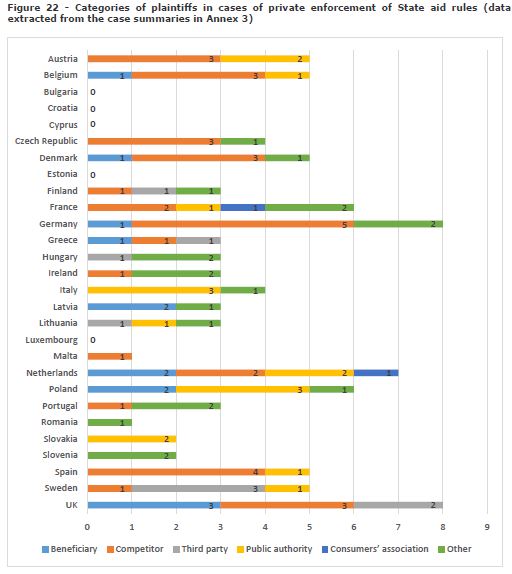

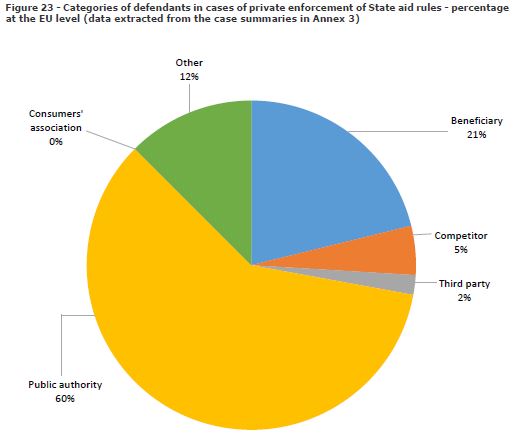

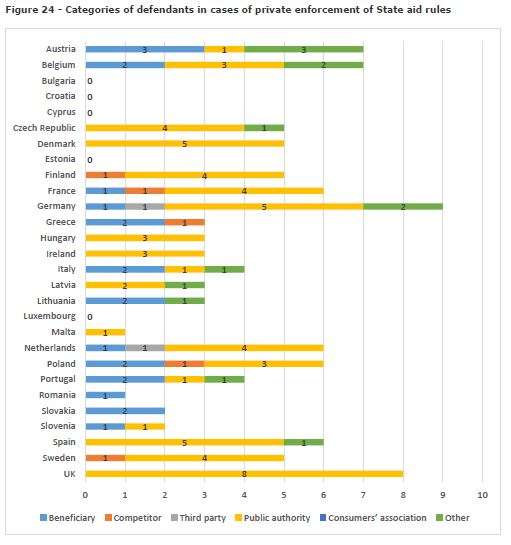

and 31 December 2017. However, the Study also includes 33 important rulings that were